Sat, Apr 27, 2024

Volume 8, Issue 4 (Autumn 2022)

Caspian J Neurol Sci 2022, 8(4): 234-243 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Naderi Nabi B, Rafiei Sorouri Z, Pourramzani A, Mirpour S H, Biazar G, Atrkarroushan Z, et al . Physicians’ Skills in Breaking Bad News to Patients With Cancer Using SPIKES Protocol. Caspian J Neurol Sci 2022; 8 (4) :234-243

URL: http://cjns.gums.ac.ir/article-1-565-en.html

URL: http://cjns.gums.ac.ir/article-1-565-en.html

Bahram Naderi Nabi *

1, Zahra Rafiei Sorouri2

1, Zahra Rafiei Sorouri2

, Ali Pourramzani3

, Ali Pourramzani3

, Seyyed Hossein Mirpour4

, Seyyed Hossein Mirpour4

, Gelareh Biazar1

, Gelareh Biazar1

, Zahra Atrkarroushan5

, Zahra Atrkarroushan5

, Morteza Mortazavi6

, Morteza Mortazavi6

, Mohadese Ahmadi1

, Mohadese Ahmadi1

1, Zahra Rafiei Sorouri2

1, Zahra Rafiei Sorouri2

, Ali Pourramzani3

, Ali Pourramzani3

, Seyyed Hossein Mirpour4

, Seyyed Hossein Mirpour4

, Gelareh Biazar1

, Gelareh Biazar1

, Zahra Atrkarroushan5

, Zahra Atrkarroushan5

, Morteza Mortazavi6

, Morteza Mortazavi6

, Mohadese Ahmadi1

, Mohadese Ahmadi1

1- Department of Anesthesiology, Anesthesiology Research Center, Faculty of Medicine, Alzahra Hospital, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran

2- Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Reproductive Health Research Center, Faculty of Medicine, Alzahra Hospital, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran

3- Cognitive and Addiction Research Center (Kavosh), Shafa Hospital, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran

4- Department of Hematology and Oncology, Faculty of Medicine, Razi Hospital, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran

5- Department of Statistic, Faculty of Health, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran

6- Student Research Committee, Faculty of Medicine, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran

2- Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Reproductive Health Research Center, Faculty of Medicine, Alzahra Hospital, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran

3- Cognitive and Addiction Research Center (Kavosh), Shafa Hospital, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran

4- Department of Hematology and Oncology, Faculty of Medicine, Razi Hospital, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran

5- Department of Statistic, Faculty of Health, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran

6- Student Research Committee, Faculty of Medicine, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran

Full-Text [PDF 1275 kb]

(598 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1068 Views)

Full-Text: (378 Views)

Introduction

Breaking bad news (BBN), which is defined as “any news that negatively affect patients’ view of future” is an unpleasant and challenging task for physicians , regardless of their [1, 2].

The issue is much more prominent among patients with cancer because, in these cases, the diagnosis of malignancy is equal to death. It has been confirmed that the quality of BBN directly affects the severity of patient’s stress and anxiety, satisfaction and coping with health outcomes and care, as well as better adaptation and acceptance [3, 4, 5]. If the patients inappropriately receive the diagnosis, it results in frustration and resistance in the patients and their relatives. It can have a negative effect on the treatment process and the patient’s health [6, 7]. It should also be noted that effective communication between physician and patient facilitates the process of obtaining informed consent, which is essential for many therapeutic interventions [8]. Disclosure of cancer diagnosis is a complex process in which medical factors, and a range of cultural, moral, and legal factors, play an essential role. Physicians must assess each patient’s willingness to receive the truth and then deliver the diagnosis with respect and sympathy [5]. Due to the importance of the topic, several recommendations have been suggested, and among them, the SPIKES protocol is the most popular one [9, 10]. This guideline has six steps to deliver bad news, particularly designed for patients with cancer [11, 12, 13]. Previous studies have demonstrated that the SPIKES protocol can be used as a framework to optimize the process of disclosure of the cancer diagnosis and leads to higher patients’ acceptance [9, 14]. In addition, studies have shown that using this protocol makes physicians feel more comfortable and confident when BBN [15]. To the best of our knowledge, the extent of compliance with this protocol has not yet been investigated in Iran, let alone in Guilan Province. Therefore, this study was designed to assess whether the patients in our province receive their cancer diagnosis based on the six SPIKES steps or not.

Materials and Methods

This descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted at academic hospitals affiliated with Guilan University of Medical Sciences (GUMS) from December 2021 to April 2022. For this study, we recruited patients above 18 years with a diagnosis of any type of malignancy within two years. They were referred to the oncology clinics of Guilan academic hospitals under the management of faculty members for follow-ups or those referred to these centers for radiotherapy and chemotherapy with the ability of proper communication. First, the purpose and method of the study were explained to the eligible patients, and informed consent was obtained. Then, the standard SPIKES questionnaire was filled out through a face-to-face interview. Based on SPIKES subscales, a questionnaire was prepared from the study of Marschollek et al. [16] and translated into Persian. The content validity index and content validity ratio were measured to evaluate the validity of the questionnaire. In this regard, ten expert faculty members of the Anesthesia Department examined the questions, and by using Lawshe’s formula, the content validity ratios for all questions was found higher than 0.62. The reliability of the questionnaire was assessed by Dorney’s similarity coefficient (the Cronbach alpha), and the content validity coefficient was found higher than 0.79. None of the panel members described the questionnaire items as irrelevant and needing serious re-evaluation.

This questionnaire consists of 12 questions in 6 sections. The first step, S (setting up), points to the environment in which the patients are informed about their diagnosis and must be private. The second step is I (invitation), which indicates the patients’ desire to know about their illnesses. The next is P (perception) which provides the opportunity to know how much information the patient has about the disease. The fourth step is K (knowledge), which emphasizes using simple and understandable terms when describing the disease to patients. The fifth step is E (emotion), the time to express empathy and try to understand and support patients’ feelings. The sixth step is S (strategy and summary) or the moment of summarizing all that has been said about the treatment strategy and prognosis [17].

Statistical analysis

The collected data were analyzed by the Chi-square test, Mann-Whitney U test, and 1-sample t-test in SPSS 21 software (IBM Corp. Released 2012. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, v. 21 Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). Significance level was considered less than 0.05.

Results

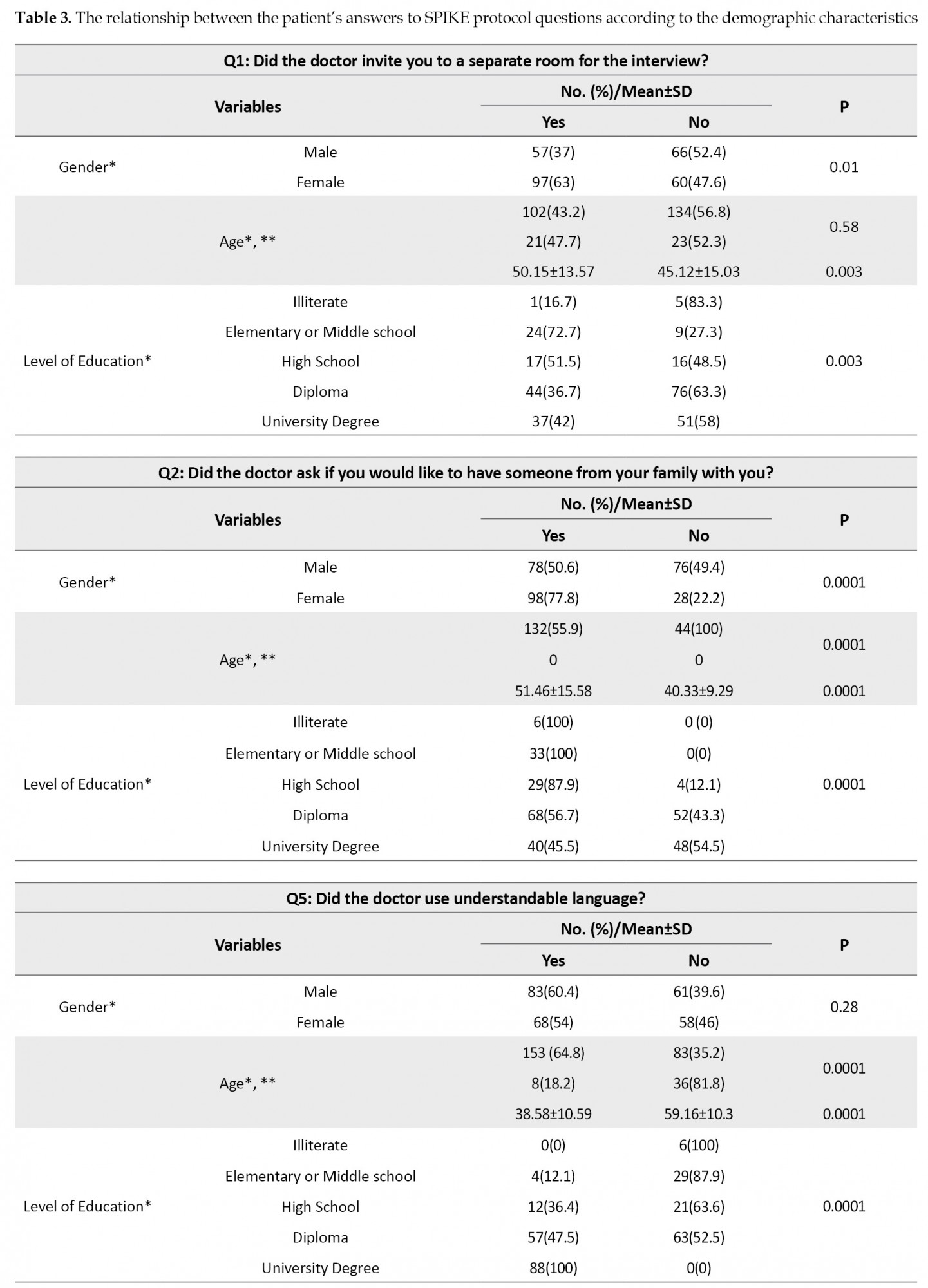

A total of 280 patients with a mean age of 47.33±14.6 years were interviewed. The patients’ demographic data are presented in Table 1.

.jpg)

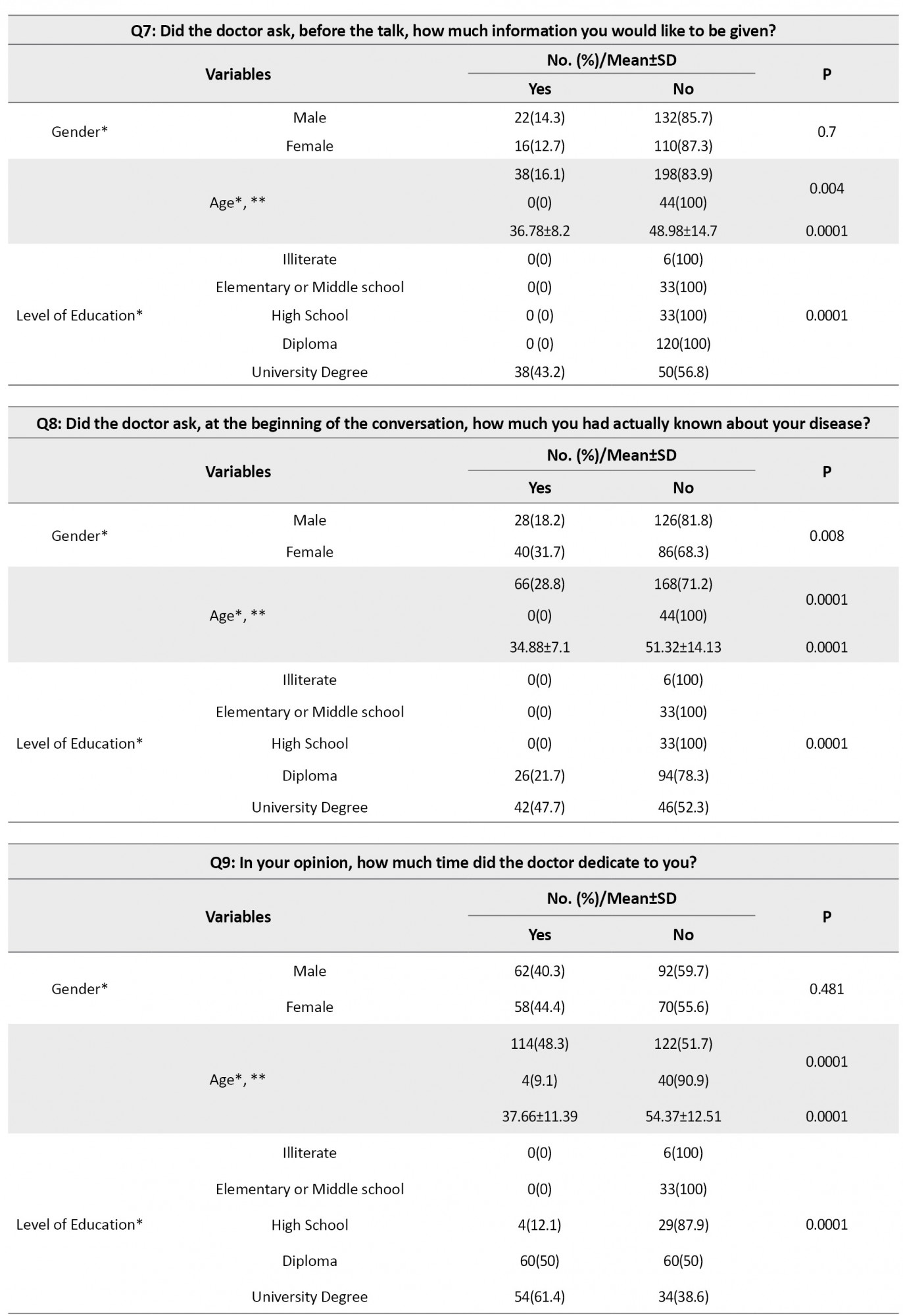

Everyone stated that at the time of receiving the diagnosis, the doctor was not in a hurry and made appropriate eye contact. However, none of them were questioned if they were ready to talk about the disease. About 61.1% believed that they were emotionally supported and that the doctor understood them. Also, 86.4% were not questioned if they wanted to know about their disease. In 75.7% of cases, physicians did not try to find out how much information the patient had about the disease. Finally, 65.4% of them were satisfied with the received information and treatment planning (Table 2).

.jpg)

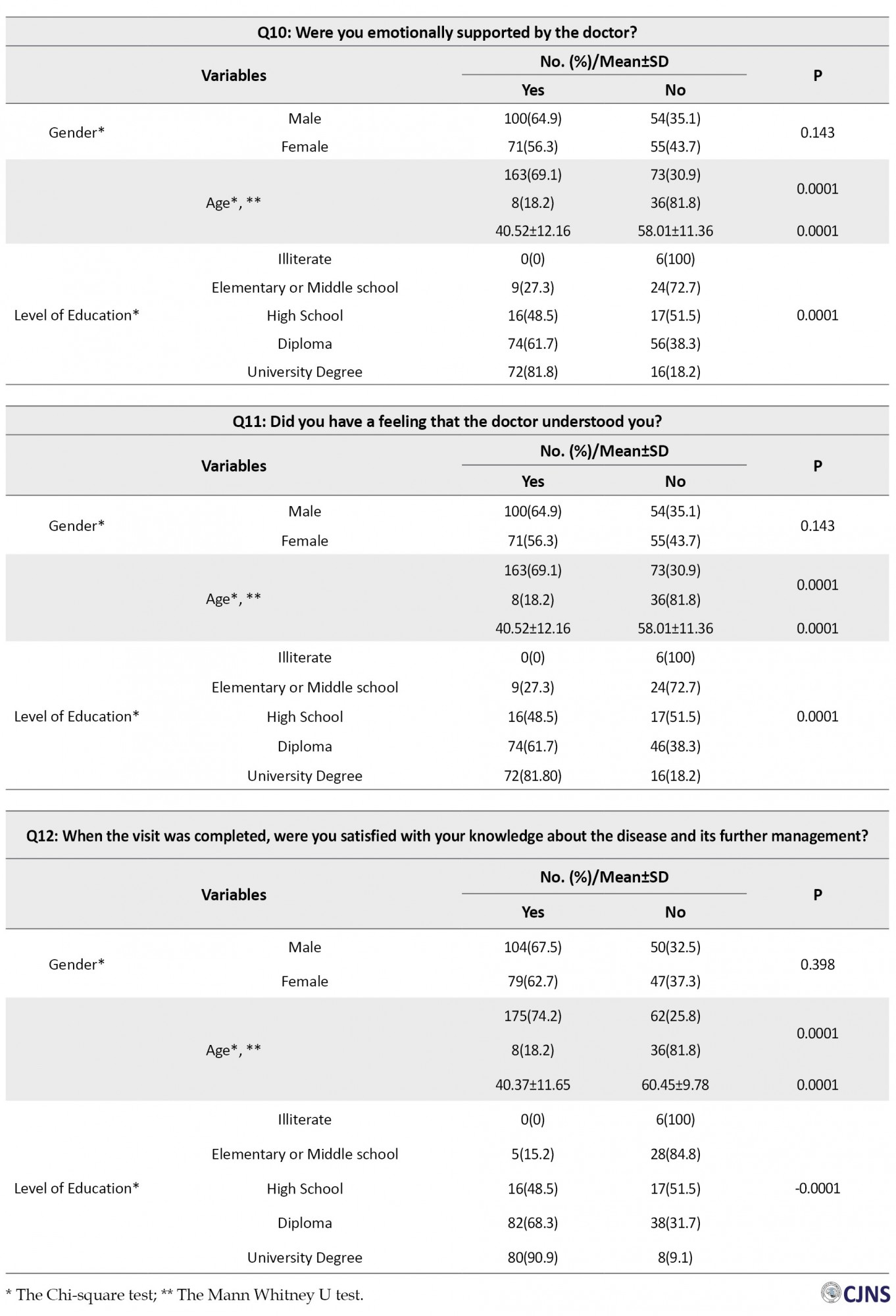

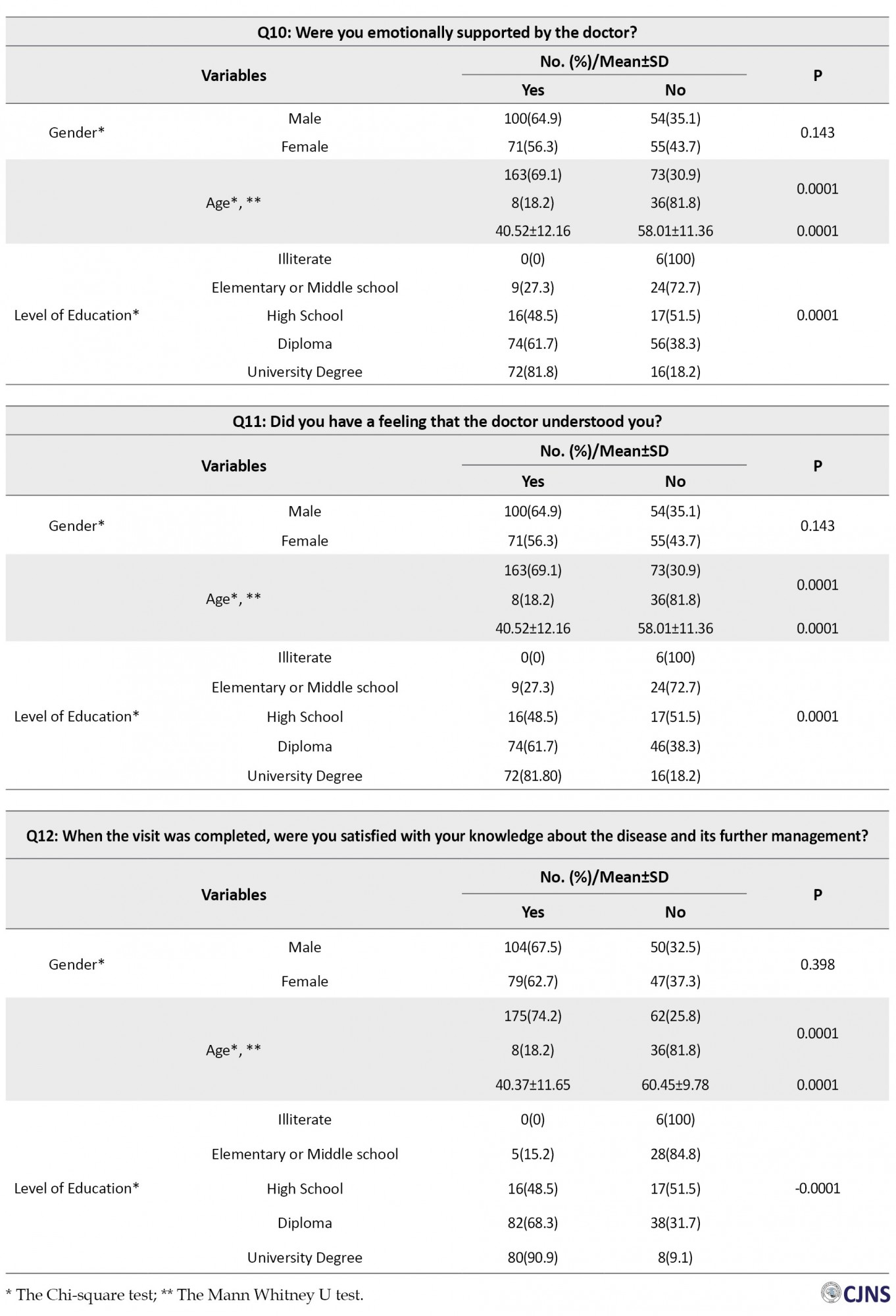

Regarding the first question of inviting patients to a separate room for the interview, a significant relationship was found between the answer “yes” and variables of female gender (P=0.01) and age under 65 years and a higher level of education (P=0.003). About the second question, whether the patient wants to be with a family member, female gender and age above 65 were significantly more questioned (P=0.0001).

Regarding the fifth question, using understandable language by physicians, patients with younger ages (P=0.0001) and higher level of education (P=0.0001) were significantly more satisfied.

Regarding the 7th question, according to the amount of information and how much information the patient wants to receive, there was a significant positive relationship between the answer “yes” and younger people (P=0.004) with a higher level of education (P=0.0001).

Regarding the 8th question, asking about how much the patients actually known about their diseases, a positive relationship was found between younger ages (P=0.004) and higher academic education (P=0.0001) and female gender (P=0.008). Regarding the 9th question, whether the interview time was sufficient or not, ages under 65 years and people with higher education (P=0.0001) were significantly more satisfied with the conversation time. About the 10th question, which was about the patients’ emotional support by doctors, ages below 65 years and a higher level of education (P=0.0001), significantly declared that they were supported well by physicians. The same pattern was followed for the 11th and 12th questions (Table 3).

Discussion

This study showed that more than half of the patients were satisfied with the information about their disease and the summary of the conversation. Almost half of them stated that the doctor did not invite them to a separate room, but at the same time, most of them considered the appropriate private conditions of the place and did not complain about the crowds. Patient’s privacy is very important and should be given enough attention. In the absence of a separate space, it is recommended that curtains should be drawn around the patient’s bed [18]. In some aspects, the doctor’s performance was acceptable and matched patients’ communication needs. For example, all patients stated that the doctor had proper eye contact with them and was calm in a sitting position, not in a rush when delivering the diagnosis. Regarding the presence of a relative next to the patient when receiving the diagnosis, one-third of the patients were not questioned. However, in most cases, one of the patient’s relatives was present at the time of conversation. Also, in many cases, the person who received the bad news was not the patient, and after the initial conversation with a close relative, the patient was informed of the diagnosis of cancer. It was revealed that none of the patients were asked whether they were mentally and emotionally prepared for the interview. In addition, most patients were not questioned whether they wanted to receive bad news and how much information they had and how much they wanted to know. Despite the emphasis on SPIKES protocol, almost all our patients did not consider it a failure and stated that there was no need for these questions. They expected the doctor to provide them with anything they actually had to know about their disease and tell them the further planning. These findings suggest that due to the basic cultural and beliefs differences [19], the current SPIKES protocol must be native to each country. We found that the elderly and lower levels of education were significantly more likely to state that physicians’ language was not comprehensive; physicians did not understand them; they were not emotionally supported, and that they were dissatisfied with their knowledge of illness and treatment planning summary. These results indicate that, this population needs special attention. More than half of the patients declared that the doctor emotionally supported them. In this process, one of the most difficult tasks for doctors is to strike a balance between giving hope and empathy but not over-closing or unrealistic expectations. The doctors should adhere to sociocultural norms and pay attention to the risk of overdoing empathy or excessive physical contact [20]. Brown et al. reported that the main reason for dissatisfaction was the unsympathetic behavior of physicians [21]. Seifart et al. conducted a similar study in Germany and reported that cancer patients were dissatisfied with how their cancer diagnosis was disclosed [18]. Mostafavian et al. assessed physicians’ skills in disclosing cancer diagnosis based on SPIKES protocol. They reported that they were not skilled enough in some aspects [22]. Simmone et al. evaluated the preferences of patients with brain tumors for receiving their diagnosis. They reported that 70% appreciated the physician’s behavior when delivering the initial diagnosis [23]. Marschollek et al. shared their experience examining cancer patients’ perspectives about receiving the diagnosis. Their survey was designed according to SPIKES guidelines. The highest scores were obtained for questions related to emotions and setting areas. They found that privacy and a more comprehensive language were very important, and physicians should consider them at the highest possible level. They found that younger individuals needed more attention and time compared to older patients which was inconsistent with our results [16]. Alnefaie et al. from Saudi Arabia reported that 38.3% of surgeons in academic hospitals were aware of the SPIKES protocol. Only 20% had received specific training courses, while most of them agreed on the necessity of improving their communication skills [24]. Fisseha et al. from Ethiopia discussed that the SPIKES protocol was poorly implemented, and only 30.6% of patients were delighted with the physicians’ communication [25]. As mentioned above, the results of studies in different areas are contradictory. Of course, the studied populations, as well as the styles and perceptions of the responsible physicians, are different. Studies have shown that the quality of the cancer diagnosis disclosure process depends on several factors, including differences in individuals’ expectations and preferences, physicians’ communication skills, patient-physician relationships, biomedical, psychological, cultural beliefs, and ethnic differences [26]. However, despite discrepancies, almost all studies have agreed on the need for communication skills training courses for medical students and post graduated physicians and report that they were not at an optimal level to delivering bad news [27]. Studies indicate that the majority of physicians have not received formal training in BBN skills; a recent systemic review concluded that regular medical curriculum should focus on the professionals items such as the BBN communication skills training [28]. A similar study conducted in Guilan academic hospitals, investigating how bad news was delivered to the patients by faculty members and residents, found that the quality of this task did not differ between those who participated in training courses with others. In contrast, years of experience were significantly associated with a higher ability to disclose bad news. Therefore, it seems that people act better according to their experience gained over the years, not educational courses, which indicates the need for a fundamental revision of this process [29].

Study suggestions

Because of the noticeable cultural, religious, and belief differences in our country, it is necessary to conduct this research in different regions. Physicians’ performance in the private sector should also be investigated. Furthermore, based on our findings on cancer patients’ perception on how they were given their diagnosis, guidance should be provided to physicians involved in such conversations.

Study limitations

This study was performed in academic hospitals, and the physicians employed in the private sector did not enroll. The recall biases and forgetfulness of all the details should also be considered.

Conclusion

According to the study results, in some areas, such as “invitation,” there was a large gap between the standards for delivering cancer diagnosis and what physicians perform. On the other hand, in some areas, such as “setting,” the results were acceptable. In addition, the elderly and illiterate people needed a simpler dialect. The final conclusion in the field of “strategy” showed that the elderly with a lower level of education were not satisfied with their knowledge about treatment planning. In some respects, such as questioning how much the patient knew and how much he wanted to know, although a tiny percentage of people were asked, they did not consider it as a failure, indicating that the recommended SPIKES protocol needs to be customized based on cultural and ecological differences.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All study procedures were in compliance with the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki (2013). The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Guilan University of Medical Sciences (GUMS) (Code: IR.GUMS.REC.1400.536).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors contributions

Study concept and design: Bahram Naderi Nabi and Zahra Rafiei Sorouri; Drafting the manuscript: Gelareh Biazar and Zahra Rafiei Sorouri; Acquisition of data: Morteza Mortazavi and Ali Pourramzani; Statistical analysis: Zahra Atrkarroushan; Analysis and interpretation of data: Seyyed Hossein Mirpour; Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors; Study supervision: Gelareh Biazar and Bahram Naderi Nabi.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank members of Anesthesiology Research Center, Guilan University of Medical Sciences (GUMS), Mohadese Ahmadi, and Mahin Tayefeh Ashrafie, for their collaboration in this study.

Breaking bad news (BBN), which is defined as “any news that negatively affect patients’ view of future” is an unpleasant and challenging task for physicians , regardless of their [1, 2].

The issue is much more prominent among patients with cancer because, in these cases, the diagnosis of malignancy is equal to death. It has been confirmed that the quality of BBN directly affects the severity of patient’s stress and anxiety, satisfaction and coping with health outcomes and care, as well as better adaptation and acceptance [3, 4, 5]. If the patients inappropriately receive the diagnosis, it results in frustration and resistance in the patients and their relatives. It can have a negative effect on the treatment process and the patient’s health [6, 7]. It should also be noted that effective communication between physician and patient facilitates the process of obtaining informed consent, which is essential for many therapeutic interventions [8]. Disclosure of cancer diagnosis is a complex process in which medical factors, and a range of cultural, moral, and legal factors, play an essential role. Physicians must assess each patient’s willingness to receive the truth and then deliver the diagnosis with respect and sympathy [5]. Due to the importance of the topic, several recommendations have been suggested, and among them, the SPIKES protocol is the most popular one [9, 10]. This guideline has six steps to deliver bad news, particularly designed for patients with cancer [11, 12, 13]. Previous studies have demonstrated that the SPIKES protocol can be used as a framework to optimize the process of disclosure of the cancer diagnosis and leads to higher patients’ acceptance [9, 14]. In addition, studies have shown that using this protocol makes physicians feel more comfortable and confident when BBN [15]. To the best of our knowledge, the extent of compliance with this protocol has not yet been investigated in Iran, let alone in Guilan Province. Therefore, this study was designed to assess whether the patients in our province receive their cancer diagnosis based on the six SPIKES steps or not.

Materials and Methods

This descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted at academic hospitals affiliated with Guilan University of Medical Sciences (GUMS) from December 2021 to April 2022. For this study, we recruited patients above 18 years with a diagnosis of any type of malignancy within two years. They were referred to the oncology clinics of Guilan academic hospitals under the management of faculty members for follow-ups or those referred to these centers for radiotherapy and chemotherapy with the ability of proper communication. First, the purpose and method of the study were explained to the eligible patients, and informed consent was obtained. Then, the standard SPIKES questionnaire was filled out through a face-to-face interview. Based on SPIKES subscales, a questionnaire was prepared from the study of Marschollek et al. [16] and translated into Persian. The content validity index and content validity ratio were measured to evaluate the validity of the questionnaire. In this regard, ten expert faculty members of the Anesthesia Department examined the questions, and by using Lawshe’s formula, the content validity ratios for all questions was found higher than 0.62. The reliability of the questionnaire was assessed by Dorney’s similarity coefficient (the Cronbach alpha), and the content validity coefficient was found higher than 0.79. None of the panel members described the questionnaire items as irrelevant and needing serious re-evaluation.

This questionnaire consists of 12 questions in 6 sections. The first step, S (setting up), points to the environment in which the patients are informed about their diagnosis and must be private. The second step is I (invitation), which indicates the patients’ desire to know about their illnesses. The next is P (perception) which provides the opportunity to know how much information the patient has about the disease. The fourth step is K (knowledge), which emphasizes using simple and understandable terms when describing the disease to patients. The fifth step is E (emotion), the time to express empathy and try to understand and support patients’ feelings. The sixth step is S (strategy and summary) or the moment of summarizing all that has been said about the treatment strategy and prognosis [17].

Statistical analysis

The collected data were analyzed by the Chi-square test, Mann-Whitney U test, and 1-sample t-test in SPSS 21 software (IBM Corp. Released 2012. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, v. 21 Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). Significance level was considered less than 0.05.

Results

A total of 280 patients with a mean age of 47.33±14.6 years were interviewed. The patients’ demographic data are presented in Table 1.

.jpg)

Everyone stated that at the time of receiving the diagnosis, the doctor was not in a hurry and made appropriate eye contact. However, none of them were questioned if they were ready to talk about the disease. About 61.1% believed that they were emotionally supported and that the doctor understood them. Also, 86.4% were not questioned if they wanted to know about their disease. In 75.7% of cases, physicians did not try to find out how much information the patient had about the disease. Finally, 65.4% of them were satisfied with the received information and treatment planning (Table 2).

.jpg)

Regarding the first question of inviting patients to a separate room for the interview, a significant relationship was found between the answer “yes” and variables of female gender (P=0.01) and age under 65 years and a higher level of education (P=0.003). About the second question, whether the patient wants to be with a family member, female gender and age above 65 were significantly more questioned (P=0.0001).

Regarding the fifth question, using understandable language by physicians, patients with younger ages (P=0.0001) and higher level of education (P=0.0001) were significantly more satisfied.

Regarding the 7th question, according to the amount of information and how much information the patient wants to receive, there was a significant positive relationship between the answer “yes” and younger people (P=0.004) with a higher level of education (P=0.0001).

Regarding the 8th question, asking about how much the patients actually known about their diseases, a positive relationship was found between younger ages (P=0.004) and higher academic education (P=0.0001) and female gender (P=0.008). Regarding the 9th question, whether the interview time was sufficient or not, ages under 65 years and people with higher education (P=0.0001) were significantly more satisfied with the conversation time. About the 10th question, which was about the patients’ emotional support by doctors, ages below 65 years and a higher level of education (P=0.0001), significantly declared that they were supported well by physicians. The same pattern was followed for the 11th and 12th questions (Table 3).

Discussion

This study showed that more than half of the patients were satisfied with the information about their disease and the summary of the conversation. Almost half of them stated that the doctor did not invite them to a separate room, but at the same time, most of them considered the appropriate private conditions of the place and did not complain about the crowds. Patient’s privacy is very important and should be given enough attention. In the absence of a separate space, it is recommended that curtains should be drawn around the patient’s bed [18]. In some aspects, the doctor’s performance was acceptable and matched patients’ communication needs. For example, all patients stated that the doctor had proper eye contact with them and was calm in a sitting position, not in a rush when delivering the diagnosis. Regarding the presence of a relative next to the patient when receiving the diagnosis, one-third of the patients were not questioned. However, in most cases, one of the patient’s relatives was present at the time of conversation. Also, in many cases, the person who received the bad news was not the patient, and after the initial conversation with a close relative, the patient was informed of the diagnosis of cancer. It was revealed that none of the patients were asked whether they were mentally and emotionally prepared for the interview. In addition, most patients were not questioned whether they wanted to receive bad news and how much information they had and how much they wanted to know. Despite the emphasis on SPIKES protocol, almost all our patients did not consider it a failure and stated that there was no need for these questions. They expected the doctor to provide them with anything they actually had to know about their disease and tell them the further planning. These findings suggest that due to the basic cultural and beliefs differences [19], the current SPIKES protocol must be native to each country. We found that the elderly and lower levels of education were significantly more likely to state that physicians’ language was not comprehensive; physicians did not understand them; they were not emotionally supported, and that they were dissatisfied with their knowledge of illness and treatment planning summary. These results indicate that, this population needs special attention. More than half of the patients declared that the doctor emotionally supported them. In this process, one of the most difficult tasks for doctors is to strike a balance between giving hope and empathy but not over-closing or unrealistic expectations. The doctors should adhere to sociocultural norms and pay attention to the risk of overdoing empathy or excessive physical contact [20]. Brown et al. reported that the main reason for dissatisfaction was the unsympathetic behavior of physicians [21]. Seifart et al. conducted a similar study in Germany and reported that cancer patients were dissatisfied with how their cancer diagnosis was disclosed [18]. Mostafavian et al. assessed physicians’ skills in disclosing cancer diagnosis based on SPIKES protocol. They reported that they were not skilled enough in some aspects [22]. Simmone et al. evaluated the preferences of patients with brain tumors for receiving their diagnosis. They reported that 70% appreciated the physician’s behavior when delivering the initial diagnosis [23]. Marschollek et al. shared their experience examining cancer patients’ perspectives about receiving the diagnosis. Their survey was designed according to SPIKES guidelines. The highest scores were obtained for questions related to emotions and setting areas. They found that privacy and a more comprehensive language were very important, and physicians should consider them at the highest possible level. They found that younger individuals needed more attention and time compared to older patients which was inconsistent with our results [16]. Alnefaie et al. from Saudi Arabia reported that 38.3% of surgeons in academic hospitals were aware of the SPIKES protocol. Only 20% had received specific training courses, while most of them agreed on the necessity of improving their communication skills [24]. Fisseha et al. from Ethiopia discussed that the SPIKES protocol was poorly implemented, and only 30.6% of patients were delighted with the physicians’ communication [25]. As mentioned above, the results of studies in different areas are contradictory. Of course, the studied populations, as well as the styles and perceptions of the responsible physicians, are different. Studies have shown that the quality of the cancer diagnosis disclosure process depends on several factors, including differences in individuals’ expectations and preferences, physicians’ communication skills, patient-physician relationships, biomedical, psychological, cultural beliefs, and ethnic differences [26]. However, despite discrepancies, almost all studies have agreed on the need for communication skills training courses for medical students and post graduated physicians and report that they were not at an optimal level to delivering bad news [27]. Studies indicate that the majority of physicians have not received formal training in BBN skills; a recent systemic review concluded that regular medical curriculum should focus on the professionals items such as the BBN communication skills training [28]. A similar study conducted in Guilan academic hospitals, investigating how bad news was delivered to the patients by faculty members and residents, found that the quality of this task did not differ between those who participated in training courses with others. In contrast, years of experience were significantly associated with a higher ability to disclose bad news. Therefore, it seems that people act better according to their experience gained over the years, not educational courses, which indicates the need for a fundamental revision of this process [29].

Study suggestions

Because of the noticeable cultural, religious, and belief differences in our country, it is necessary to conduct this research in different regions. Physicians’ performance in the private sector should also be investigated. Furthermore, based on our findings on cancer patients’ perception on how they were given their diagnosis, guidance should be provided to physicians involved in such conversations.

Study limitations

This study was performed in academic hospitals, and the physicians employed in the private sector did not enroll. The recall biases and forgetfulness of all the details should also be considered.

Conclusion

According to the study results, in some areas, such as “invitation,” there was a large gap between the standards for delivering cancer diagnosis and what physicians perform. On the other hand, in some areas, such as “setting,” the results were acceptable. In addition, the elderly and illiterate people needed a simpler dialect. The final conclusion in the field of “strategy” showed that the elderly with a lower level of education were not satisfied with their knowledge about treatment planning. In some respects, such as questioning how much the patient knew and how much he wanted to know, although a tiny percentage of people were asked, they did not consider it as a failure, indicating that the recommended SPIKES protocol needs to be customized based on cultural and ecological differences.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All study procedures were in compliance with the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki (2013). The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Guilan University of Medical Sciences (GUMS) (Code: IR.GUMS.REC.1400.536).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors contributions

Study concept and design: Bahram Naderi Nabi and Zahra Rafiei Sorouri; Drafting the manuscript: Gelareh Biazar and Zahra Rafiei Sorouri; Acquisition of data: Morteza Mortazavi and Ali Pourramzani; Statistical analysis: Zahra Atrkarroushan; Analysis and interpretation of data: Seyyed Hossein Mirpour; Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors; Study supervision: Gelareh Biazar and Bahram Naderi Nabi.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank members of Anesthesiology Research Center, Guilan University of Medical Sciences (GUMS), Mohadese Ahmadi, and Mahin Tayefeh Ashrafie, for their collaboration in this study.

References

- Buckman R. How to break bad news: A guide for health care professionals. Toronto: University of Toronto Press; 1992. [DOI:10.3138/9781487596989]

- Cassim S, Kidd J, Keenan R, Middleton K, Rolleston A, Hokowhitu B, et al. Indigenous perspectives on breaking bad news: Ethical considerations for healthcare providers. J Med Ethics. 2021; 47:e62. [DOI:10.1136/medethics-2020-106916] [PMID]

- Alnefaie S, Filfilan NN, Altalhi EA, Al Juaid RS, Aljuaid ND, Abdulrahman R. Evaluation of surgeons’ skills in breaking bad news to cancer patients based on the SPIKES protocol in multiple medical centers at Taif city, Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional study. Int J Med Dev Ctries. 2021; 5(1):49-51. [DOI:10.24911/IJMDC.51-1603221074]

- Anuk D, Alçalar N, Sağlam EK, Bahadır G. Breaking bad news to cancer patients and their families: Attitudes toward death among Turkish physicians and their communication styles. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2022; 40(1):115-30. [DOI:10.1080/07347332.2021.1969488] [PMID]

- Wu J, Wang Y, Jiao X, Wang J, Ye X, Wang B. Differences in practice and preferences associated with truth-telling to cancer patients. Nurs Ethics. 2021; 28(2):272-81. [DOI:10.1177/0969733020945754] [PMID]

- Hobenu KA, Naab F. Accessing specialist healthcare: Experiences of women diagnosed with advanced cervical cancer in Ghana. Br J Healthc Manag. 2022; 28(2):1-11. [DOI:10.12968/bjhc.2021.0054]

- Monden KR, Gentry L, Cox TR. Delivering bad news to patients. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2016; 29(1):101-2. [DOI:10.1080/08998280.2016.11929380] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Abraha Woldemariam A, Andersson R, Munthe C, Linderholm B, Berbyuk Lindström N. Breaking bad news in cancer care: Ethiopian patients want more information than what family and the public want them to have. JCO Glob Oncol. 2021; 7:1341-8. [DOI:10.1200/GO.21.00190] [PMID] [PMCID]

- von Blanckenburg P, Hofmann M, Rief W, Seifart U, Seifart C. Assessing patients´ preferences for breaking Bad News according to the SPIKES-protocol: The MABBAN scale. Patient Educ Couns. 2020; 103(8):1623-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.pec.2020.02.036] [PMID]

- Carver C. The fear of dying: A case study using the SPIKES protocol. Fam Soc. 2018; 99(4):333-7. [DOI:10.1177/1044389418803444]

- Baile WF, Buckman R, Lenzi R, Glober G, Beale EA, Kudelka AP. SPIKES-A six-step protocol for delivering bad news: Application to the patient with cancer. Oncologist. 2000; 5(4):302-11. [DOI:10.1634/theoncologist.5-4-302] [PMID]

- Fan Z, Chen L, Meng L, Jiang H, Zhao Q, Zhang L, et al. Preference of cancer patients and family members regarding delivery of bad news and differences in clinical practice among medical staff. Support Care Cancer. 2019; 27(2):583-9. [DOI:10.1007/s00520-018-4348-1] [PMID]

- Labaf A, Jahanshir A, Shahvaraninasab A. [Difficulties in using Western guidelines for breaking bad news in the emergency department: The necessity of indigenizing guidelines for non-Western countries (Persian)]. Iran J Med Ethics Hist Med. 2014; 7(1):4-11. [Link]

- Bai S, Wu B, Yao Z, Zhu X, Jiang Y, Chang Q, et al. Effectiveness of a modified doctor-patient communication training program designed for surgical residents in China: A prospective, large-volume study at a single Centre. BMC Med Edu. 2019; 19(1):338. [DOI:10.1186/s12909-019-1776-7] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Ferreira da Silveira FJ, Botelho CC, Valadão CC. Breaking bad news: Doctors’ skills in communicating with patients. Sao Paulo Med J. 2017; 135(4):323-31. [DOI:10.1590/1516-3180.20160221270117] [PMID]

- Marschollek P, Bąkowska K, Bąkowski W, Marschollek K, Tarkowski R. Oncologists and breaking bad news-from the informed patients’ point of view. The evaluation of the SPIKES protocol implementation. J Cancer Educ. 2019; 34(2):375-80. [DOI:10.1007/s13187-017-1315-3] [PMID]

- Meitar D, Karnieli-Miller O. Twelve tips to manage a breaking bad news process: Using SPw-ICE-S-A revised version of the SPIKES protocol. Medi Teac. 2021; 1-5. [DOI:10.1080/0142159X.2021.1928618] [PMID]

- Seifart C, Hofmann M, Bär T, Riera Knorrenschild J, Seifart U, Rief W. Breaking bad news-what patients want and what they get: Evaluating the SPIKES protocol in Germany. Ann Oncol. 2014; 25(3):707-11. [DOI:10.1093/annonc/mdt582] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Holmes SN, Illing J. Breaking bad news: Tackling cultural dilemmas. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2021; 11(2):128-32. [DOI:10.1136/bmjspcare-2020-002700] [PMID]

- Matthews T, Baken D, Ross K, Ogilvie E, Kent L. The experiences of patients and their family members when receiving bad news about cancer: A qualitative meta‐synthesis. Psycho‐Oncology. 2019; 28(12):2286-94. [DOI:10.1002/pon.5241] [PMID]

- Brown SD, Callahan MJ, Browning DM, Lebowitz RL, Bell SK, Jang J, et al. Radiology trainees’ comfort with difficult conversations and attitudes about error disclosure: Effect of a communication skills workshop. J Am Coll Radiol. 2014; 11(8):781-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.jacr.2014.01.018] [PMID]

- Mostafavian Z, Shaye ZA. Evaluation of physicians’ skills in breaking bad news to cancer patients. J Family Med Prim Care. 2018; 7(3):601-5. [DOI:10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_25_18] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Goebel S, Mehdorn HM. Breaking bad news to patients with intracranial tumors: The patients’ perspective. World Neurosurg. 2018; 118:e254-62. [DOI:10.1016/j.wneu.2018.06.168] [PMID]

- Alnefaie S, Filfilan NN, Altalhi EA, Al Juaid RS, Aljuaid ND, Abdulrahman R. Evaluation of surgeons’ skills in breaking bad news to cancer patients based on the SPIKES protocol in multiple medical centers at Taif city, Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Medicine in Developing Countries. 2021;5(1):51-49. [DOI:10.24911/IJMDC.51-1603221074]

- Fisseha H, Mulugeta W, Kassu RA, Geleta T, Desalegn H. Perspectives of protocol based breaking bad news among medical patients and physicians in a teaching hospital, Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2020; 30(6):1017-26. [DOI:10.4314/ejhs.v30i6.21] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Von Blanckenburg P, Hofmann M, Rief W, Seifart U, Seifart C. Assessing patients´ preferences for breaking Bad News according to the SPIKES-Protocol: the MABBAN scale. Patient Educ Couns. 2020; 103(8):1623-1629. [DOI:10.1016/j.pec.2020.02.036]. [PMID]

- Azadi A, Abdekhoda M, Habibi S. Medical student’s skills in notifying bad news based on SPIKES protocol. J Liaquat Uni Med Health Sci. 2018; 17(4):249-54. [DOI:10.22442/jlumhs.181740587]

- Camargo NC, Lima MGd, Brietzke E, Mucci S, Góis AFTd. Teaching how to deliver bad news: A systematic review. Revista Bioética. 2019; 27:326-40. [DOI:10.1590/1983-80422019272317]

- Biazar G, Delpasand K, Farzi F, Sedighinejad A, Mirmansouri A, Atrkarroushan Z. Breaking bad news: A valid concern among clinicians. Iran J Psychiatry. 2019; 14(3):198-202. [DOI:10.18502/ijps.v14i3.1321] [PMID] [PMCID]

Type of Study: Research |

Subject:

Special

Received: 2022/09/14 | Accepted: 2022/09/28 | Published: 2022/09/28

Received: 2022/09/14 | Accepted: 2022/09/28 | Published: 2022/09/28

| Rights and permissions | |

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |