Tue, Jul 9, 2024

Volume 5, Issue 4 (Autumn 2019)

Caspian J Neurol Sci 2019, 5(4): 175-184 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Shayegh Borojeni B, Manshaee G, Sajjadian I. The Effectiveness of Adolescent-centered Mindfulness Training and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy on Depression and Suicidal Ideation in Adolescent Girls With Bipolar II Disorder. Caspian J Neurol Sci 2019; 5 (4) :175-184

URL: http://cjns.gums.ac.ir/article-1-292-en.html

URL: http://cjns.gums.ac.ir/article-1-292-en.html

1- Department of Psychology, Isfahan (Khorasgan) branch, Islamic Azad University, Isfahan, Iran

Full-Text [PDF 1577 kb]

(1295 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (3137 Views)

This scale highly correlates (range: 0.90-0.94) with standardized tests of depression and suicidal tendency. Also, a correlation in the range of 0.58-0.69 was observed in BSSI questions. The validity of the scale was obtained using Cronbach alpha coefficients 0.87-0.97 and was 0.54 using the test-retest method [27]. In Iran, Anisi et al. validated the Beck questionnaire on soldiers [28]. The results showed that the concurrent validity of the scale is 0.76, and its validity by Cronbach alpha is 0.95. In this study, the Cronbach alpha coefficient was 0.96.

Results

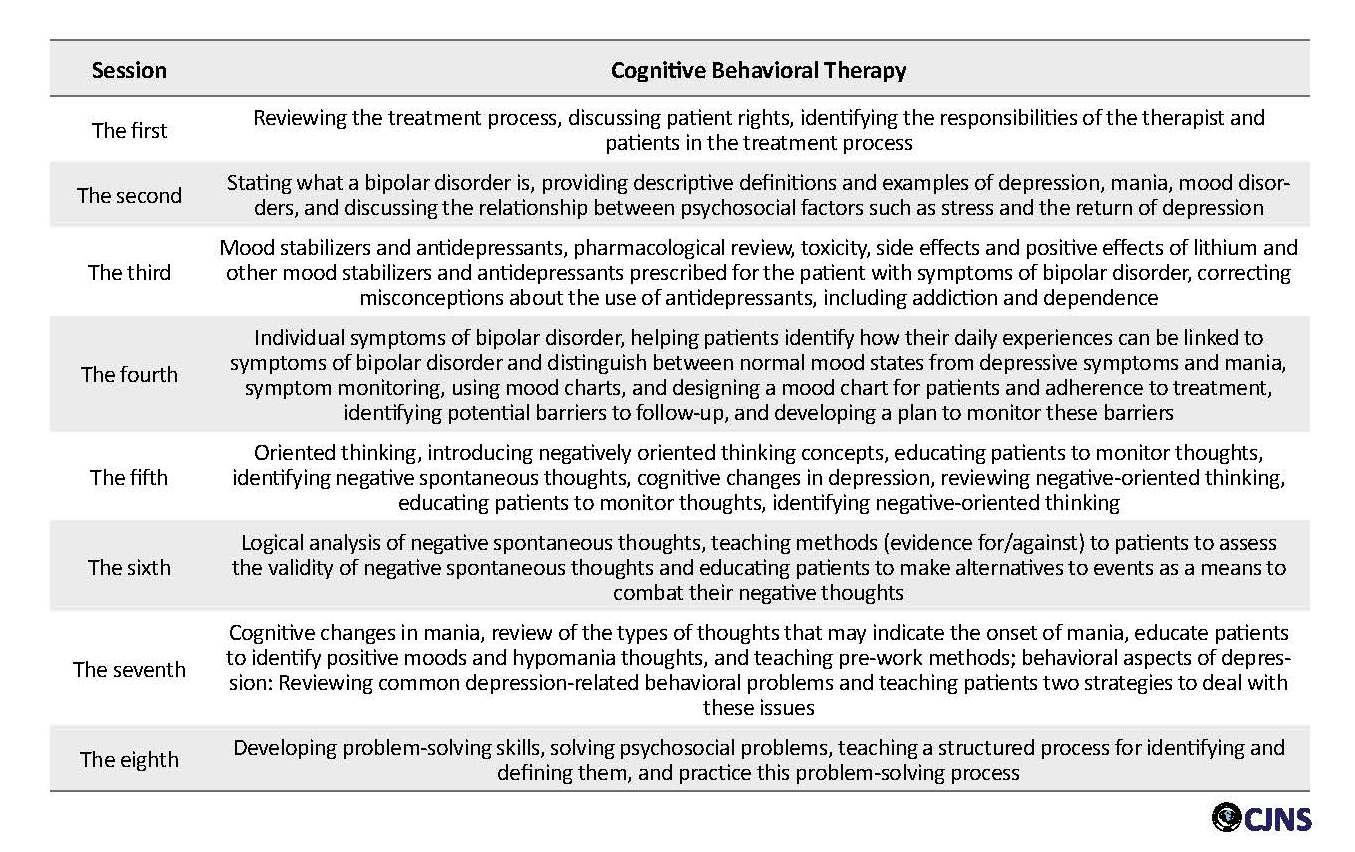

Table 2 presents the descriptive findings of the research variables in the intervention and control groups. As seen in Table 2, the mean scores of the research variables, including suicidal ideations and depression in the post-test and follow-up stages in the intervention groups were significantly lower than those in the control group. Using covariance analysis requires assumptions, including normal distribution of scores, homogeneity of variances (checked by using Levene’s test), homogeneity of regression slope (checked by pre-test interaction), and independent variable.

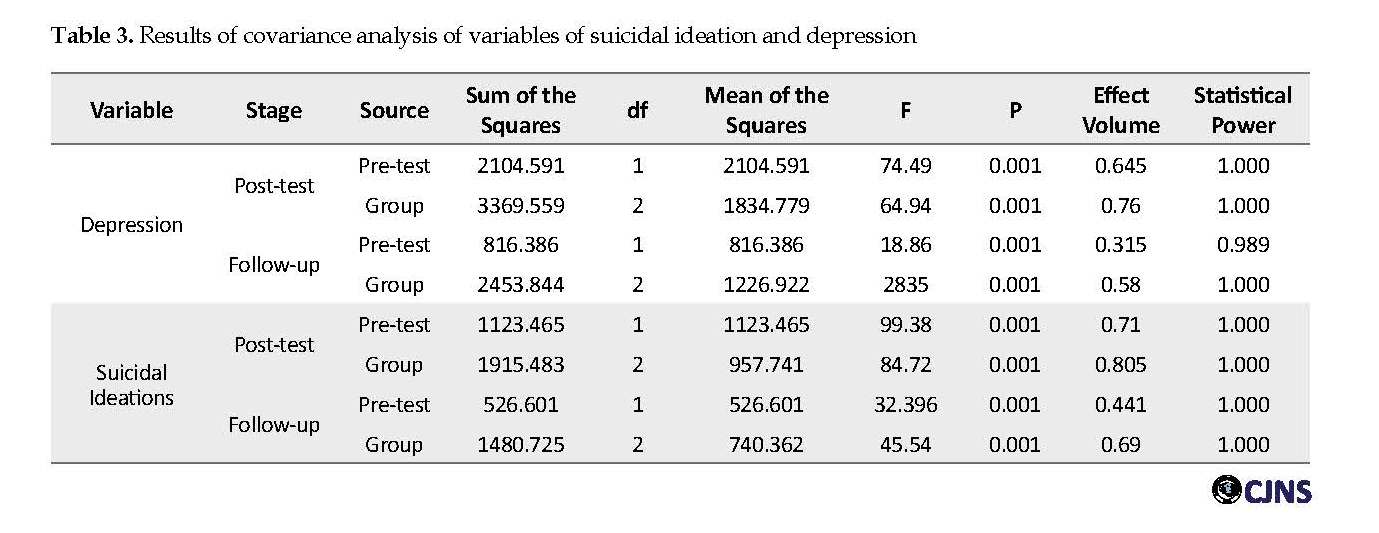

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test results showed that the null hypothesis of a normal distribution of scores in all variables in all three groups and at all three stages of research was confirmed (P>0.05). The Levene’s test results showed that in the post-test stage there was a significant difference in suicidal ideations (F=0.73; P=0.488) and depression (F=1.66; P=0.202), also in the follow-up phase variables of suicidal ideation (F=2.24; P=0.119), depression (F=3.02; P=0.054) were obtained. Also, the results confirmed the assumption of the equality of variances. Hypothesis of regression slope showed that group interaction test, pre-test, post-test in suicidal ideations (F=0.811; P=0.452), depression (F=0.575; P=0.568), and at follow-up this assumption confirmed the suicidal ideations (F=2.026; P=0.145) and depression (F=1.64; P=0.206). Table 3 presents the results of covariance analysis for comparing the research variables among three groups.

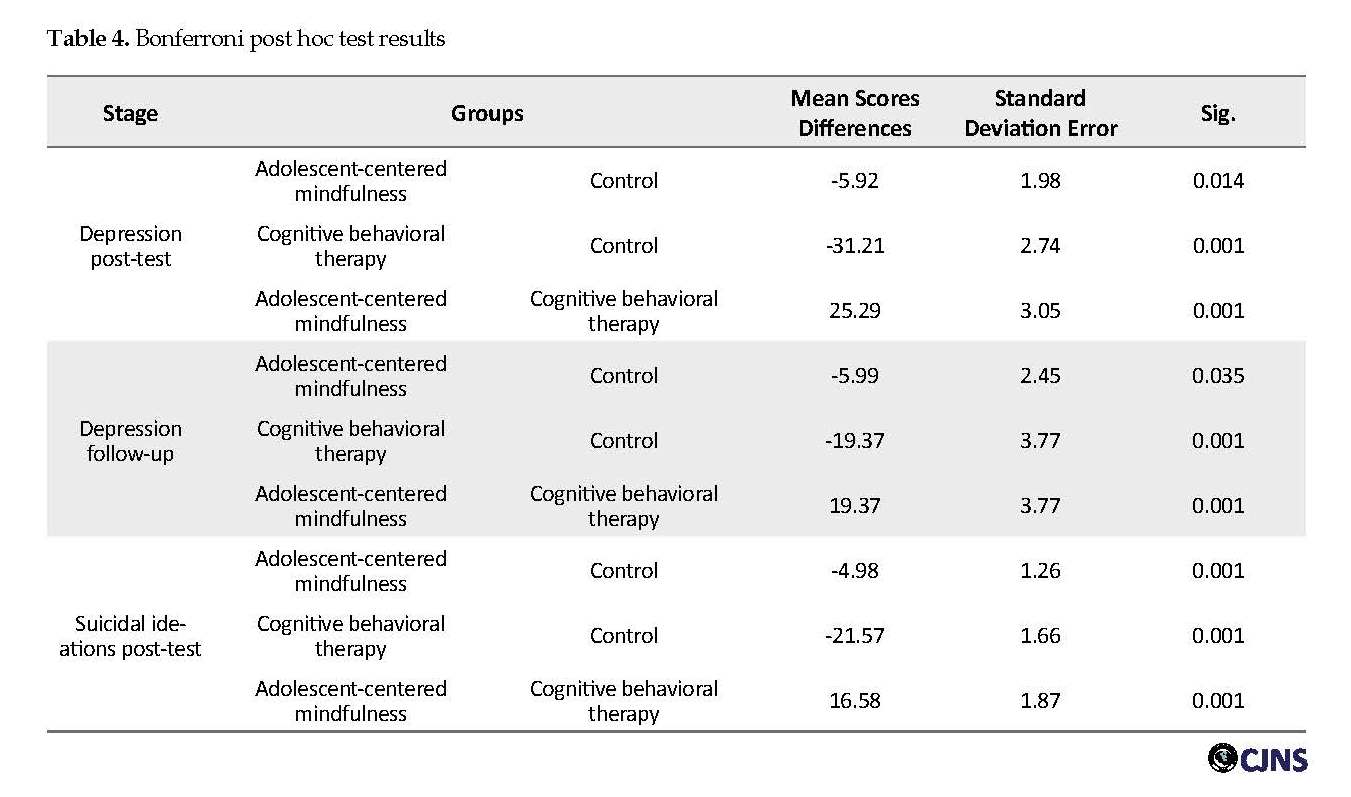

Table 3 shows that the mean scores of depression and suicidal ideation in the experimental and control groups at post-test and follow-up stages were significant by pre-test control of these variables (P<0.001). In other words, adolescent-centered mindfulness training and cognitive behavioral therapy have substantial effects on depression and suicidal ideation in adolescents with bipolar disorder in both post-test and follow-up stages. The impact of therapeutic interventions on depression was 76% in the post-test and 58% in the follow-up. However, the effect of therapeutic interventions on reducing suicidal ideations in the post-test is 80.5% and in follow-up 69%. Table 4 presents the results of the Bonferroni post hoc test to compare the mean scores of the research variables in the three groups.

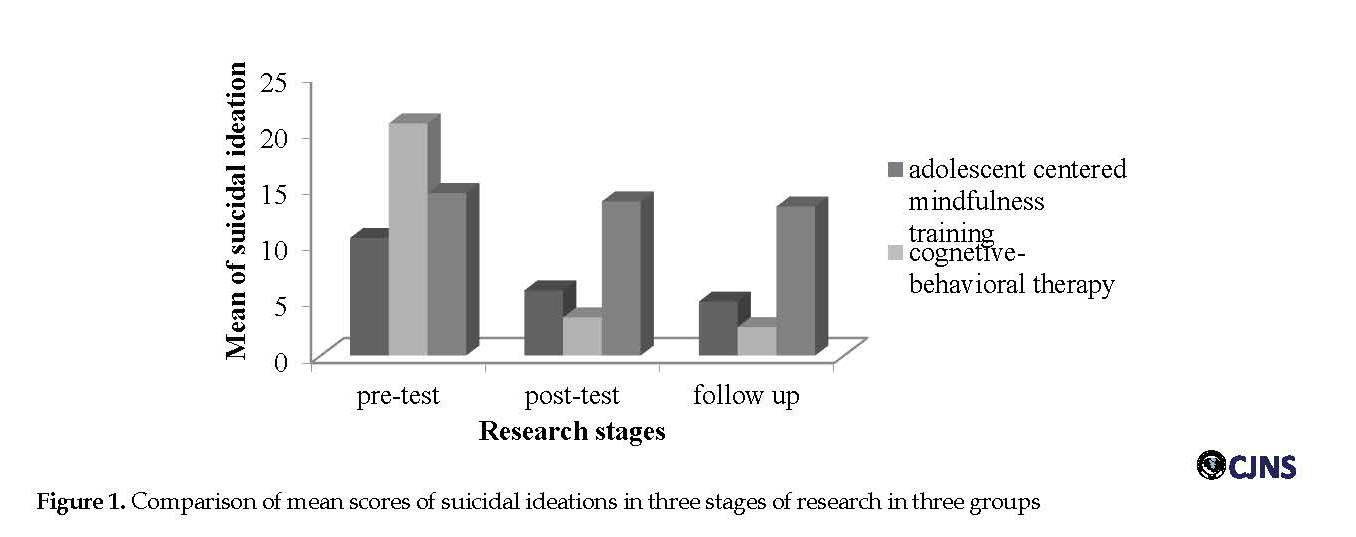

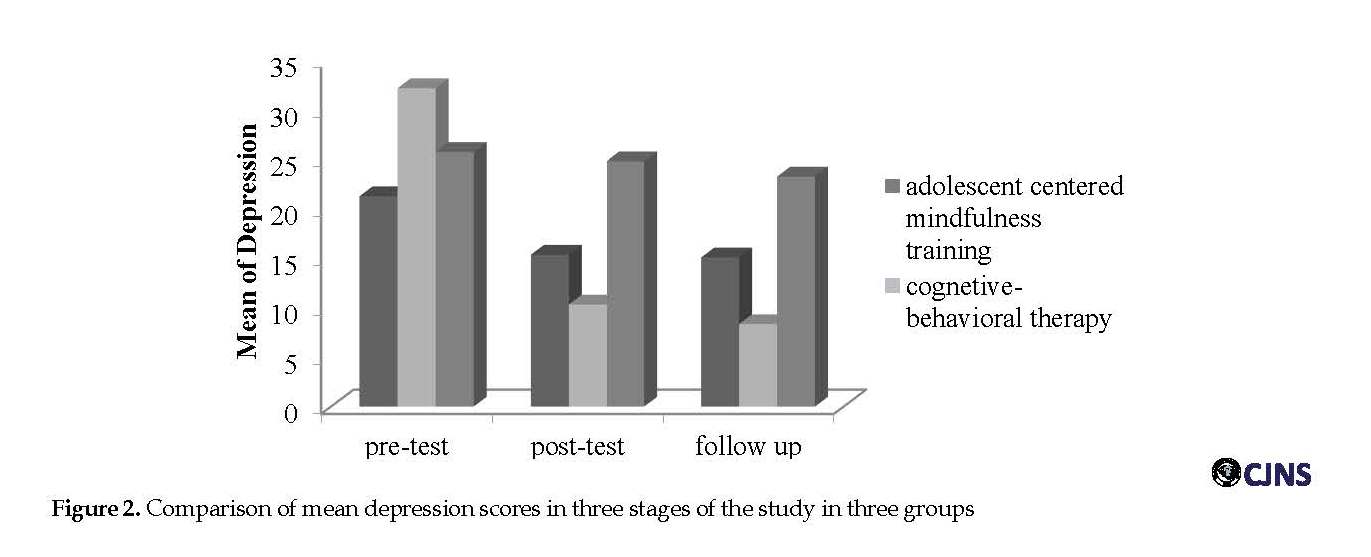

Table 4 shows that in both depression and suicidal ideations variables in the post-test and follow-up phase, there were significant differences between the control group and adolescent mindfulness training group (P<0.05) and also between the control group with the cognitive behavioral therapy group. Significant differences were also found between adolescent-centered mindfulness and cognitive behavioral therapy groups in both variables at post-test and follow-up stages (P<0.001). Figures 1 and 2 show the mean scores of the research variables in the three stages of pre-test, post-test, and follow-up in the three groups of adolescent-centered mindfulness, cognitive behavioral therapy, and control.

As seen in Figure 1 and Figure 2, both the suicidal ideation and depression mean scores of the cognitive behavioral therapy group were lower than those in the mindfulness therapy group. Thus, it seems that the effect of mindfulness training and cognitive behavioral therapy was significant on depression and suicidal ideations in adolescent girls with bipolar disorder in the post-test phase. Cognitive behavioral therapy was more effective in both of these variables in both the post-test and follow-up stages of adolescent-centered mindfulness training.

Discussion

Bipolar disorder is a chronic and debilitating disease that disrupts patients’ social functioning. In this study, we compared cognitive behavioral therapy with mindfulness therapy to improve depression symptoms, and suicidal ideation in adolescent girls with bipolar disorder, and the results showed that both adolescents’ mindfulness training and cognitive therapy intervention were effective in improving suicidal ideation and depression in both post-test and follow-up stages. However, the effect of cognitive behavioral therapy on both variables was greater in both stages. The findings of the study are consistent with Jannetti et al., Hollon, Tice, and Markowitz, and Townsend, regarding the efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy on the improvement of various symptoms of bipolar disorder [20-22].

Regarding the effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy, changing the way of thinking and behaving, cognitive behavioral therapy has fundamental effects on one’s emotional states and changes in depression and anxiety [29]. In other words, based on a cognitive perspective, disorders are the result of false, unrealistic, and irrational beliefs. Cognitive perspectives, such as the psychodynamic perspective, focus on internal flows as causes of disorders, but instead of emphasizing the desires, needs, and motivations, they believe that individuals interpret the information received and use it to solve life’s problems.

The cognitive perspective generally focuses on one’s current thoughts and solutions rather than one’s history. This means that one’s cognitive history, attitudes, and his or her present mood are considered as causes of disorders [30]. This treatment helps clients identify automatic thoughts, images, or thoughts that trigger the disorders, observe the rationale and misconceptions underlying these thoughts, and test their validity [31].

The cognitive behavioral therapy model emphasizes three main strategies of training, cognitive restructuring, and life skills intervention. In training methods, individuals are taught to identify and deal with high-risk situations that increase the likelihood of loss of control or threat of return. Cognitive restructuring is about changing one’s perception of abstinence or slip. If it does come back, instead of treating it as a personal failure that leads to internal guilt and attribution. The patient is taught to “rebuild this event as a single, independent event, and to call it an error, not a disaster that can never be overcome”. Teaching problem-solving skills to adolescents provides essential skills to solve social problems without resorting to aggression, and empathy training in schools, especially in adolescence, can reduce aggressive behaviors. Using empathy, one can identify the consequences of their behavior and thereby respond to the demands of others [32].

The findings of the present study on the efficacy of adolescent-centered mindfulness therapy are consistent with the results of Zeidan et al., who have shown that mindfulness improves mood, and short-term use of it could reduce fatigue and anxiety. Likewise, the findings of Chow et al. and Seigel showed that mindfulness-based interventions were effective in patients with bipolar disorder and would reduce anxiety and depression in them [16-18].

Concerning this finding, mind control skills learned in mindfulness can prevent the recurrence of major depression. In this treatment, people do not judge their thoughts and feelings and view them as mental events that are on the move and do not necessarily represent aspects of themselves or reality. In this approach, it is assumed that individuals learn how not to get caught up in their malicious thought patterns [33].

Mindfulness is taught through a series of tasks that are self-conscious. Each exercise can intentionally and consciously increase the capacity and ability of the information system. Mindfulness exercises can act as an early warning system to prevent a blast or an imminent flood. Mindfulness training requires metacognitive learning and new behavioral strategies to focus on attention, avoid malicious thoughts, and the tendency toward worrying responses. It also promotes new thinking and reduces emotions.

One of the fundamental orientations of mindfulness consciousness is focusing on the “present moment”. This “here and now” orientation has been effective in helping patients with cancer and chronic pain [34]. When the subjects are aware of the present, their attention is no longer focused on the past or the future; thus, suicidal ideations reduce, while most of the psychological problems rooted in focusing on their past.

In explaining the efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy rather than mindfulness therapy in improving depression and suicidal ideation in the study sample, symptoms of bipolar disorder are often characterized by inhibition, lack of energy, and apathy, all of which are behavioral symptoms; therefore, it is better to prioritize these behavioral methods [35]. Behavioral therapies are more effective in controlling patients’ lives after they have been stabilized with the help of medication. Also, Mansell et al. suggested that cognitive behavioral therapy was useful in the treatment of bipolar disorder for several reasons [36]. First, because of its mental training nature that makes it suitable for the chronic and recurrent disease through promotion, revision, and self-regulation; second, because of its proven efficacy in adhering to treatment; and third is the efficacy of therapy in preventing the relapse.

Based on the study results, we suggest that cognitive behavioral therapy be used in counseling and psychotherapy centers (clinical settings) for adolescent girls with bipolar disorder II to reduce suicidal ideation and depression and to organize counselors and therapists with this approach. It is also recommended that these approaches be tested on other groups to validate them with greater confidence. Other tools, besides questionnaires, should also be used to collect data. On the other hand, any research has its limitations, and the interpretation of the results should be considered in light of these limitations. One of the limitations of this study is the generalization of these results to other groups, as the statistical population of this study was female adolescents with bipolar II disorder.

Conclusion

The results showed that both adolescent-centered mindfulness training and cognitive behavioral therapy significantly reduced suicidal ideation and depression in adolescents with bipolar disorder in the post-test and follow-up stages. Besides, cognitive behavioral therapy in both post-test and follow-up stages was more effective than adolescent-centered mindfulness training in reducing adolescent suicidal ideation and depression.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (Code: No.IR.IAU.KHUISF.REC.1397.028). All the study procedures were in compliance with the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki (2013 revision).

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors contributions

Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content, final approval of the study, conception and design of the study, collection: Bahar Shayegh Borojeni; Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content, final approval of the study, analysis and interpretation of data, collection, and provision of patients: Gholamreza Manshaee; Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content, final approval of the study: Illnaz Sajjadian.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest

References

American Psychiatric Association (APA). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition, (DSM-5). Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association (APA); 2013.

Shaw JA, EJA EJ. A 10-years prospective study of prodromal patterns of bipolar disorder among Amish youth. J Am Acad Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2005; 44(11): 1104-11. [DOI:10.1097/01.chi.0000177052.26476.e5] [PMID]

Swann AC. Mechanisms of impulsivity in bipolar disorder and related illness. Epid Psychiatry Soc. 2010; 19(2):120-30. [DOI:10.1017/S1121189X00000828] [PMID]

Manshee gH, Hoseini L. The effectiveness of child-centered mindfulness training on social adjustment and depression symptoms in children with depression. JEEP . 2018; 29(8):179-200.

Shakibaii fEM. Epidemiology of depression in Isfahan middle school students in 2007-2008. Behav Sci Res. 2014; 12(2):274-84.

Conus P, Ward J, Hallam KT, Lucas N, Macneil C, McGorry PD, et al. The proximal prodrome to first episode mania - a new target for early intervention. Bipolar Disorders. 2008; 10(5):555-65. [DOI:10.1111/j.1399-5618.2008.00610.x] [PMID]

Lewis L, Judd MD, Hagop S, Akiskal MD, Pamela J. Schettler, et al. A prospective investigation of the natural history of the long-term weekly symptomatic status of bipolar II disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003; 60(3):261-9. [DOI:10.1001/archpsyc.60.3.261] [PMID]

Bridge GB. Adolescent suicide and suicidal behavio. child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006; 47(3-4):372-94. [DOI:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01615.x] [PMID]

Liu X TJ. Life events, psychopathology, and suicidal behavior in Chinese adolescents. Affe Dis. 2005; 86(2-3):195-203. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2005.01.016] [PMID]

Nouk M. Suicide [Internet]. 2006 [updated 2014 July]. Avalible from: http://www.teenshealth.com

Zaretsky A. Targeted psychosocial intervention for bipolar disorder. Bip Dis. 2003; 5(2):80-7. [DOI:10.1111/j.1399-2406.2003.00057.x] [PMID]

Roth BR. Mindfulnessbased stress reduction and health related quality of life. Psyc Med. 2004; 66(1):113-23. [DOI:10.1097/01.PSY.0000097337.00754.09] [PMID]

Semple R, Lee J. Mindfulness based congnitive therapy for children. In: Baer RA, editor. Mindfulness-Based Treatment Approaches. New York: Application Across the LIFESPAN; 2014. [DOI:10.1016/B978-0-12-416031-6.00008-6]

Amber S, Emanuel J, Updegraff D, Kalmbach J, Ciesla. The role of mindfulness facets in affective forecasting. Pers and Ind Diff. 2010; 49(17):815-818. [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2010.06.012]

Burdick D. Mindfulness for kids & teens: A workbook for clinicians & clients with 154 Tools, techniques, activities & worksheets. Wisconsin: PESI Publishing & Media; 2014.

Zeidan F, Johnson SK, Diamond BJ, David Z, Goolkasian P. Mindfulness meditation improves cognition: Evidence of brief mental training. Consc Cog. 2010; 19(2):597-605. [DOI:10.1016/j.concog.2010.03.014] [PMID]

Siegel L. The mindfulness Solution, every day practices for every day problems. Los Angeles: Guilford Press; 2010.

Chu CS, Stubbs B, Chen TY, Tang CH, Li DJ, Yang WC. The effectiveness of adjunet mindfulness - based intervention in tretment of bipolar disorder: Asystematic review andmeta -analysis. J of Affe Dis. 2018; 225: 234-45. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2017.08.025] [PMID]

Siotis P. Cognitive-behavioral therapy: Applications for the management of bipolar disorder. Bip Dis. 2001; 3(1):1-10. [DOI:10.1034/j.1399-5618.2001.030101.x] [PMID]

Jannati sh, Hosseini F, Kashani A, Seifi H. [The effectiveness of group therapy on cognitive - behavioral therapy on depression and anxiety an self esteem in patients with type I disease disorder (Persian)]. Princ Ment Health. 2017; 19(2):108-13.

Hollon SD, Thase ME, Markowitz JC. treatment and prevention of depression. Psychol Sci. 2002; 3(2):39-40. [DOI:10.1111/1529-1006.00008] [PMID]

Townsend DSN, Mary C. Essential of psychiatric mental heath nursing. Philadelphia: Davis Company; 2008.

Bordeaux. A guide to teaching minfulness skills to childrenand young people. Edinburgh: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2017.

Basco MRA. Cognitive behavioral therapy for Bipolar disorder, 2nd Edition. New-York: Guiford Press; 2007.

Salehzadeh M. [Effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy on depression and quality of life in patients with drug resistant epilepsy in Isfahan (Persian)] [MSc. thesis]. Isfahan: Isfahan University; 2008.

Fathi Ashtiyani A. [Psychological Test- Personality Evaluation and mental Health (Persian)]. Tehran: Besat Publications; 2007.

Beck AT, Steer RA. Beck Anxiety Inventory Manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation Harcourt Brace & Company; 1993.

Anisi J, Fathi Ashtiyani A, Salimi Sh, Ahmadi Kh. Validity and reability of Beck suicidal thought in soldiers. Mil Med. 2003; 33(7):1-37.

Morrison AP. A casebook of cognitive therapy for psychosis. 1st ed. New York: Brunner-Routledge Taylor and Francis Group; 2002.

Azad H. [Abnormal psychology (Persian)]. Tehran: Besat Publications; 2008.

Dadsetan P. [Developmental abnormal psychology (Persian)]. Tehran: SAMT; 2008.

Maina G, Rosso A, Aguglia DF, Chiodelli F, Bogetto. Anxiety and bipolar disorders: Epidemiological and clinical aspects. Giorn Ital Psicopat. 2011; 17:365-75.

Teasdale JD, Moore RG, Hayhurst H, Pope M, Williams S, Segal ZV. Metacognitive awareness and prevention of relapse in depression: Empirical evidence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002; 70(2):275-87. [DOI:10.1037//0022-006X.70.2.275] [PMID]

Speca M, Carleson LE, Mackenzie MJ, Angen M. Mingfulnessstress duction (MBSR) as an interventionfor cancer patients. In: bear. R. editor. Mindfulness based treatment approaches. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2006. [DOI:10.1016/B978-012088519-0/50012-5]

Zaretsky AE, Segal ZV, Gemar M. Cognitive therapy for Bipolar depression: A pilot study. Can J Psychiatry. 1999; 44(5):491-4. [DOI:10.1177/070674379904400511] [PMID]

Mansell W, Colom F, Scott J. The nature and treatment of depression in Bipolar disorder: A review and implications for future psychological investigation. Clin Psychol Rev. 2005; 25(8):1076-100. [DOI:10.1016/j.cpr.2005.06.007] [PMID]

Full-Text: (1116 Views)

Introduction

Bipolar disorder is one of the most common mood disorders that affects the patient’s functioning, interpersonal interactions, and quality of life. Bipolar I disorder consists of a period of mania that can occur before or after periods of hypomania or major depression. In bipolar II disorder, a person does not go through a full course of manic periods; he or she only experiences severe depression in acute hypomanic episodes [1].

In one study, it is found that 1% of adolescents have bipolar II disorder, of whom 5.6% suffer from significant but less than subthreshold symptoms [2]. Symptoms of this disorder include a set of clinical conditions associated with mood disorders, lack of control over mood and subjective experience, and severe discomfort [1]. Adolescents with bipolar disorder usually change rapidly from mania to depression [3]. Depression can be defined as a disordered mood and emotional state characterized by sleep disturbances, anorexia, decreased libido, impaired interest in and enjoyment of routine activities, feelings of worthlessness and guilt, feelings of severe sadness, and preferring loneliness [4].

Studies show that the prevalence of moderate or severe depression in adolescents is about 2.3 to 5.9 in 10000 people, 100000 people, or percent, etc [5]. In many bipolar patients, the period of depression is the first symptom of the disease, and the patient experiences several periods of depression at the onset of the disorder before the first period of mania and hypomania. In general, in addition to adversely affecting the emotions and the physique, depression has adverse effects on daily activities, habits, and patient’s relationships [6]. Studies show that the episode of depression in bipolar disorder is more frequent and prolonged than mania and hypomania periods [7].

Suicidal ideation is defined as a range of thoughts, images, and ideas related to a suicide attempt or desire to discontinue living with no suicidal attempt [8]. Research findings indicate that the most important psychological factors underlying suicide include mood disorders, substance abuse, hopelessness, low self-esteem, inhibition of internal control, recent stressful events, and inadequate social support [9].

Adolescence is not easy period of life. there are many social, educational, and personal pressures in this period that are all are new and make life harder for teens who may have other problems, such as mental illness. Adolescents with bipolar disorder are at higher risk for suicide since they are in a state of severe depression, and at the same time, they are highly energetic, which affects their mood, vision, and judgment. All of these affections lead them to suicidal ideation and suicide [10].

Although drug therapy is the main treatment for bipolar disorder, studies in recent years have shown that psychosocial interventions increase the efficacy of the treatment program [11]. One of the treatments is currently applied alongside drug treatment for patients with bipolar disorder is adolescent-centered mindfulness training therapy. Mindfulness refers to an experience in which the individual comes to his knowledge, in a specific, purposeful, at the present moment, and free of internal-external judgments [12].

Practicing mindfulness can lead to changes in thinking patterns or changes in attitudes about one’s thoughts. It helps one to understand that negative emotions may occur, but they are not a permanent component of personality [13]. Mindfulness research suggests that its practice changes the brain in positive ways, helps to develop and stabilize the mood, reinforces emotional regulation, and strengthens the self-esteem of adolescents who are vulnerable during this period. It also helps adolescents with bipolar disorder make positive changes in themselves by combining vitality and vivid experiences to achieve happiness and well-being.

In general, practicing mindfulness can change patterns of thought or one’s attitude and ideas. In other words, the person clings to his or her thoughts, feelings, and imaginations and do not associate them with one’s self. Additionally, the adolescent does not seek his or her identity in them. This notion is essential because, if properly understood, it can make a remarkable difference in one’s life [14].

Child-centered and adolescent-centered mindfulness is one of the newest methods that its clinical application has been useful for children with dysfunctional problems, inadequate attention, hyperactivity, depression, anxiety, traumatic stress, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and aggression [15]. Various studies have reflected that mindfulness training improves mood, reduces sadness, depression, insomnia, anxiety, and depression in bipolar patients [16-18].

Cognitive behavioral therapies are considered as conventional treatments for anxiety problems and should be regarded as the first line of treatments. Also, cognitive behavioral therapy has been the first choice for bipolar disorder treatment for a number of reasons: First because of the nature of psychotherapeutic training that by upgrading, revising, and self-regulating tries to treat chronic and recurrent disorders; second its proven efficacy in increasing adherence to drug therapy; and thirdly, the results of studies suggest that the interaction between cognitive style and stressful events can predict the semiotics of depression. This reason may support cognitive behavioral therapy use for bipolar disorder since the methodology of cognitive style plays a significant role in these disorders [19].

In their study, Jannati et al. investigated the effect of cognitive behavioral group therapy on depression, anxiety, and self-esteem in patients with bipolar I disorder [20]. They reported that cognitive behavioral treatment had a significant impact on depression and anxiety in bipolar patients. Holon, Tice, and Markowitz studied the treatment and prevention of depression by introducing various effective therapies for the treatment of depression and bipolar disorder. They found that cognitive behavioral therapy alone or in combination with drug therapy is the most effective treatment for preventing relapse of bipolar I and II symptoms in people with these disorders [21]. Townsend argued that cognitive group therapy after drug therapy is the second most commonly used treatment in patients with bipolar disorder, which in some cases, is even more effective than drug therapy [22].

To summarize, so far, specialists have used several types of psychological treatment to improve the condition of patients with bipolar disorder. They tried to identify other therapies along with medications to help patients with bipolar disorder; these new therapies should be useful and low-cost. Considering the prevalence of this disorder and its complications, especially in adolescents, as well as the lack of research in this field, we aimed to compare the effectiveness of adolescent-centered mindfulness therapy with cognitive behavioral therapy on depression and suicidal ideations among adolescent girls with bipolar II disorder.

Materials and Methods

Research type, sample, and sampling method

The method of this study is quasi-experimental with pre-test, post-test design and a control group with 45-days follow-up. The statistical population consisted of all adolescent girls with bipolar II disorder referred to Al-Zahra Hospital during spring and summer of 2018. We used the convenience sampling method to select study samples from all young female patients with bipolar II disorder referred to Al-Zahra Hospital. Eventually, a total of 45 subjects were selected and then randomly divided into three groups (every group with 15 subjects): one control group and two experimental groups. The inclusion criteria included subjects with bipolar II disorder approved by a psychiatrist, age range 14-17 years, female, and consumer of mood stabilizer psychiatric medications. The exclusion criteria included absence for at least two sessions from the treatment program and having other psychiatric disorders diagnosed by a psychiatrist.

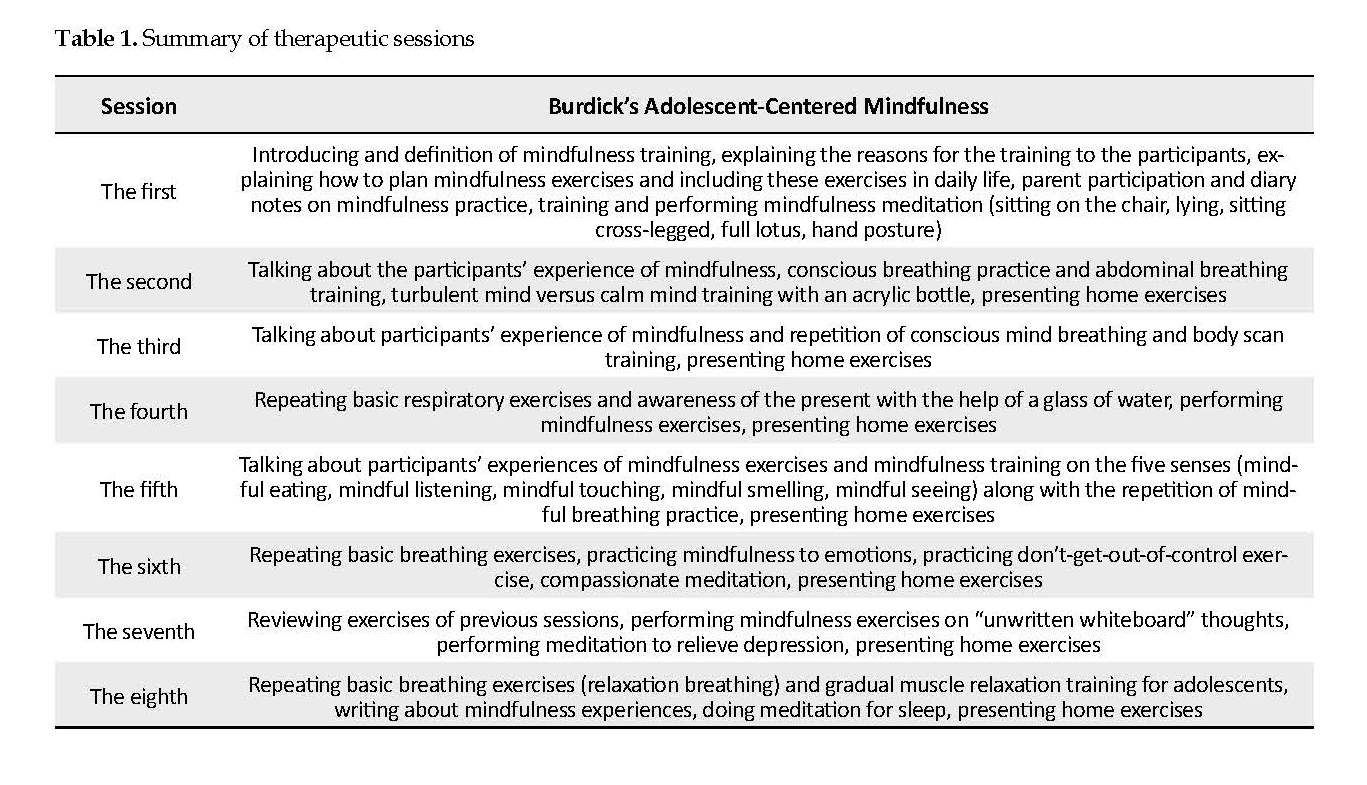

The first experimental group received adolescent-centered mindfulness training drawn from Burdick’s adolescent mindfulness therapy (Table 1) for 8 one-hour sessions [15, 23]. In each session, techniques and exercises related to that session were used. At the end of each session, assignments were given. In the last session, a post-test was performed. The second experimental group received cognitive behavioral therapy based on the Basque and Rush therapy sessions (Table 1) for 8 one-hour sessions [24]. Each session uses the techniques and exercises of that session. At the end of each session, assignments were also given. In the last session, the post-test was taken. No intervention was performed for the control group during this period. All three groups answered the research questionnaires before and immediately after treatment sessions and then after 45 days of follow-up.

Research tools

Beck depression inventory

This test was developed in 1961 by Beck et al. and revised in 1974 [25]. The questionnaire is one of the most appropriate tools for reflecting depression and contains 21 items that measure the physical, behavioral, and cognitive symptoms of depression. Each item has 4 options that determine different degrees of depression from mild to severe. The questionnaire deals more with measuring the psychological characteristics of depression than physical and physiological distress, with a correlation of 0.75 with the Hamilton questionnaire. The 21 items of the Beck Depression Inventory are classified into 3 groups of affective, cognitive, and physical symptoms [1]. Each item has four sentences that measure the severity of depression, and each sentence scores from 0 to 3. The lowest total score is 0, and the highest is 63. Interpreting the results, the degrees of depression are as follows: 0-4 probable denial, 5-9 very mild depression, 10-18 mild to moderate depression, 19-29 moderate to severe depression, and more than 30 severe depression.

The results of the meta-analysis on Beck Depresson Inventory (BDI) indicate that its internal consistency coefficient ranges from 0.73 to 0.93 with a mean value of 0.86, and its alpha coefficient was reported 0.86 for the patient and 0.81 for the non-patient group. In a study on the students of Tehran and Allameh Tabatabae’i universities who performed the second version of the BDI to evaluate the validity and reliability of the Iranian population, the Cronbach alpha of the inventory was found as 0.78 with test-retest reliability of 0.73 within two weeks [26]. In this study, the Cronbach alpha coefficient for this questionnaire was 0.91.

beak suicide scale ideations

In 1961, Aaron Beck developed the Beak Suicide Scale Ideations (BSSI), which contains 19 items. This scale was designed to reveal and measure the severity of attitudes, behaviors, and to plan for suicide over the past week. The scale is scored from 0 to 2. The overall score for the individual is calculated based on the sum of the scores and ranges from 0 to 38. The scores between 0 and 3 indicate no suicidal ideation, scores between 4 and 11 show low suicidal ideations, and the score 12 or more indicate high-risk suicidal ideations. The scale measures items such as death wish, active and or passive tendency to suicide, duration, and ideations of suicide, self-control, suicide deterrent factors, and readiness to commit suicide. There are five questions in BSSI called screening questions. If the answers indicate an active or inactive suicidal tendency, then the respondent is expected to answer the following 14 questions.

Bipolar disorder is one of the most common mood disorders that affects the patient’s functioning, interpersonal interactions, and quality of life. Bipolar I disorder consists of a period of mania that can occur before or after periods of hypomania or major depression. In bipolar II disorder, a person does not go through a full course of manic periods; he or she only experiences severe depression in acute hypomanic episodes [1].

In one study, it is found that 1% of adolescents have bipolar II disorder, of whom 5.6% suffer from significant but less than subthreshold symptoms [2]. Symptoms of this disorder include a set of clinical conditions associated with mood disorders, lack of control over mood and subjective experience, and severe discomfort [1]. Adolescents with bipolar disorder usually change rapidly from mania to depression [3]. Depression can be defined as a disordered mood and emotional state characterized by sleep disturbances, anorexia, decreased libido, impaired interest in and enjoyment of routine activities, feelings of worthlessness and guilt, feelings of severe sadness, and preferring loneliness [4].

Studies show that the prevalence of moderate or severe depression in adolescents is about 2.3 to 5.9 in 10000 people, 100000 people, or percent, etc [5]. In many bipolar patients, the period of depression is the first symptom of the disease, and the patient experiences several periods of depression at the onset of the disorder before the first period of mania and hypomania. In general, in addition to adversely affecting the emotions and the physique, depression has adverse effects on daily activities, habits, and patient’s relationships [6]. Studies show that the episode of depression in bipolar disorder is more frequent and prolonged than mania and hypomania periods [7].

Suicidal ideation is defined as a range of thoughts, images, and ideas related to a suicide attempt or desire to discontinue living with no suicidal attempt [8]. Research findings indicate that the most important psychological factors underlying suicide include mood disorders, substance abuse, hopelessness, low self-esteem, inhibition of internal control, recent stressful events, and inadequate social support [9].

Adolescence is not easy period of life. there are many social, educational, and personal pressures in this period that are all are new and make life harder for teens who may have other problems, such as mental illness. Adolescents with bipolar disorder are at higher risk for suicide since they are in a state of severe depression, and at the same time, they are highly energetic, which affects their mood, vision, and judgment. All of these affections lead them to suicidal ideation and suicide [10].

Although drug therapy is the main treatment for bipolar disorder, studies in recent years have shown that psychosocial interventions increase the efficacy of the treatment program [11]. One of the treatments is currently applied alongside drug treatment for patients with bipolar disorder is adolescent-centered mindfulness training therapy. Mindfulness refers to an experience in which the individual comes to his knowledge, in a specific, purposeful, at the present moment, and free of internal-external judgments [12].

Practicing mindfulness can lead to changes in thinking patterns or changes in attitudes about one’s thoughts. It helps one to understand that negative emotions may occur, but they are not a permanent component of personality [13]. Mindfulness research suggests that its practice changes the brain in positive ways, helps to develop and stabilize the mood, reinforces emotional regulation, and strengthens the self-esteem of adolescents who are vulnerable during this period. It also helps adolescents with bipolar disorder make positive changes in themselves by combining vitality and vivid experiences to achieve happiness and well-being.

In general, practicing mindfulness can change patterns of thought or one’s attitude and ideas. In other words, the person clings to his or her thoughts, feelings, and imaginations and do not associate them with one’s self. Additionally, the adolescent does not seek his or her identity in them. This notion is essential because, if properly understood, it can make a remarkable difference in one’s life [14].

Child-centered and adolescent-centered mindfulness is one of the newest methods that its clinical application has been useful for children with dysfunctional problems, inadequate attention, hyperactivity, depression, anxiety, traumatic stress, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and aggression [15]. Various studies have reflected that mindfulness training improves mood, reduces sadness, depression, insomnia, anxiety, and depression in bipolar patients [16-18].

Cognitive behavioral therapies are considered as conventional treatments for anxiety problems and should be regarded as the first line of treatments. Also, cognitive behavioral therapy has been the first choice for bipolar disorder treatment for a number of reasons: First because of the nature of psychotherapeutic training that by upgrading, revising, and self-regulating tries to treat chronic and recurrent disorders; second its proven efficacy in increasing adherence to drug therapy; and thirdly, the results of studies suggest that the interaction between cognitive style and stressful events can predict the semiotics of depression. This reason may support cognitive behavioral therapy use for bipolar disorder since the methodology of cognitive style plays a significant role in these disorders [19].

In their study, Jannati et al. investigated the effect of cognitive behavioral group therapy on depression, anxiety, and self-esteem in patients with bipolar I disorder [20]. They reported that cognitive behavioral treatment had a significant impact on depression and anxiety in bipolar patients. Holon, Tice, and Markowitz studied the treatment and prevention of depression by introducing various effective therapies for the treatment of depression and bipolar disorder. They found that cognitive behavioral therapy alone or in combination with drug therapy is the most effective treatment for preventing relapse of bipolar I and II symptoms in people with these disorders [21]. Townsend argued that cognitive group therapy after drug therapy is the second most commonly used treatment in patients with bipolar disorder, which in some cases, is even more effective than drug therapy [22].

To summarize, so far, specialists have used several types of psychological treatment to improve the condition of patients with bipolar disorder. They tried to identify other therapies along with medications to help patients with bipolar disorder; these new therapies should be useful and low-cost. Considering the prevalence of this disorder and its complications, especially in adolescents, as well as the lack of research in this field, we aimed to compare the effectiveness of adolescent-centered mindfulness therapy with cognitive behavioral therapy on depression and suicidal ideations among adolescent girls with bipolar II disorder.

Materials and Methods

Research type, sample, and sampling method

The method of this study is quasi-experimental with pre-test, post-test design and a control group with 45-days follow-up. The statistical population consisted of all adolescent girls with bipolar II disorder referred to Al-Zahra Hospital during spring and summer of 2018. We used the convenience sampling method to select study samples from all young female patients with bipolar II disorder referred to Al-Zahra Hospital. Eventually, a total of 45 subjects were selected and then randomly divided into three groups (every group with 15 subjects): one control group and two experimental groups. The inclusion criteria included subjects with bipolar II disorder approved by a psychiatrist, age range 14-17 years, female, and consumer of mood stabilizer psychiatric medications. The exclusion criteria included absence for at least two sessions from the treatment program and having other psychiatric disorders diagnosed by a psychiatrist.

The first experimental group received adolescent-centered mindfulness training drawn from Burdick’s adolescent mindfulness therapy (Table 1) for 8 one-hour sessions [15, 23]. In each session, techniques and exercises related to that session were used. At the end of each session, assignments were given. In the last session, a post-test was performed. The second experimental group received cognitive behavioral therapy based on the Basque and Rush therapy sessions (Table 1) for 8 one-hour sessions [24]. Each session uses the techniques and exercises of that session. At the end of each session, assignments were also given. In the last session, the post-test was taken. No intervention was performed for the control group during this period. All three groups answered the research questionnaires before and immediately after treatment sessions and then after 45 days of follow-up.

Research tools

Beck depression inventory

This test was developed in 1961 by Beck et al. and revised in 1974 [25]. The questionnaire is one of the most appropriate tools for reflecting depression and contains 21 items that measure the physical, behavioral, and cognitive symptoms of depression. Each item has 4 options that determine different degrees of depression from mild to severe. The questionnaire deals more with measuring the psychological characteristics of depression than physical and physiological distress, with a correlation of 0.75 with the Hamilton questionnaire. The 21 items of the Beck Depression Inventory are classified into 3 groups of affective, cognitive, and physical symptoms [1]. Each item has four sentences that measure the severity of depression, and each sentence scores from 0 to 3. The lowest total score is 0, and the highest is 63. Interpreting the results, the degrees of depression are as follows: 0-4 probable denial, 5-9 very mild depression, 10-18 mild to moderate depression, 19-29 moderate to severe depression, and more than 30 severe depression.

The results of the meta-analysis on Beck Depresson Inventory (BDI) indicate that its internal consistency coefficient ranges from 0.73 to 0.93 with a mean value of 0.86, and its alpha coefficient was reported 0.86 for the patient and 0.81 for the non-patient group. In a study on the students of Tehran and Allameh Tabatabae’i universities who performed the second version of the BDI to evaluate the validity and reliability of the Iranian population, the Cronbach alpha of the inventory was found as 0.78 with test-retest reliability of 0.73 within two weeks [26]. In this study, the Cronbach alpha coefficient for this questionnaire was 0.91.

beak suicide scale ideations

In 1961, Aaron Beck developed the Beak Suicide Scale Ideations (BSSI), which contains 19 items. This scale was designed to reveal and measure the severity of attitudes, behaviors, and to plan for suicide over the past week. The scale is scored from 0 to 2. The overall score for the individual is calculated based on the sum of the scores and ranges from 0 to 38. The scores between 0 and 3 indicate no suicidal ideation, scores between 4 and 11 show low suicidal ideations, and the score 12 or more indicate high-risk suicidal ideations. The scale measures items such as death wish, active and or passive tendency to suicide, duration, and ideations of suicide, self-control, suicide deterrent factors, and readiness to commit suicide. There are five questions in BSSI called screening questions. If the answers indicate an active or inactive suicidal tendency, then the respondent is expected to answer the following 14 questions.

This scale highly correlates (range: 0.90-0.94) with standardized tests of depression and suicidal tendency. Also, a correlation in the range of 0.58-0.69 was observed in BSSI questions. The validity of the scale was obtained using Cronbach alpha coefficients 0.87-0.97 and was 0.54 using the test-retest method [27]. In Iran, Anisi et al. validated the Beck questionnaire on soldiers [28]. The results showed that the concurrent validity of the scale is 0.76, and its validity by Cronbach alpha is 0.95. In this study, the Cronbach alpha coefficient was 0.96.

Results

Table 2 presents the descriptive findings of the research variables in the intervention and control groups. As seen in Table 2, the mean scores of the research variables, including suicidal ideations and depression in the post-test and follow-up stages in the intervention groups were significantly lower than those in the control group. Using covariance analysis requires assumptions, including normal distribution of scores, homogeneity of variances (checked by using Levene’s test), homogeneity of regression slope (checked by pre-test interaction), and independent variable.

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test results showed that the null hypothesis of a normal distribution of scores in all variables in all three groups and at all three stages of research was confirmed (P>0.05). The Levene’s test results showed that in the post-test stage there was a significant difference in suicidal ideations (F=0.73; P=0.488) and depression (F=1.66; P=0.202), also in the follow-up phase variables of suicidal ideation (F=2.24; P=0.119), depression (F=3.02; P=0.054) were obtained. Also, the results confirmed the assumption of the equality of variances. Hypothesis of regression slope showed that group interaction test, pre-test, post-test in suicidal ideations (F=0.811; P=0.452), depression (F=0.575; P=0.568), and at follow-up this assumption confirmed the suicidal ideations (F=2.026; P=0.145) and depression (F=1.64; P=0.206). Table 3 presents the results of covariance analysis for comparing the research variables among three groups.

Table 3 shows that the mean scores of depression and suicidal ideation in the experimental and control groups at post-test and follow-up stages were significant by pre-test control of these variables (P<0.001). In other words, adolescent-centered mindfulness training and cognitive behavioral therapy have substantial effects on depression and suicidal ideation in adolescents with bipolar disorder in both post-test and follow-up stages. The impact of therapeutic interventions on depression was 76% in the post-test and 58% in the follow-up. However, the effect of therapeutic interventions on reducing suicidal ideations in the post-test is 80.5% and in follow-up 69%. Table 4 presents the results of the Bonferroni post hoc test to compare the mean scores of the research variables in the three groups.

Table 4 shows that in both depression and suicidal ideations variables in the post-test and follow-up phase, there were significant differences between the control group and adolescent mindfulness training group (P<0.05) and also between the control group with the cognitive behavioral therapy group. Significant differences were also found between adolescent-centered mindfulness and cognitive behavioral therapy groups in both variables at post-test and follow-up stages (P<0.001). Figures 1 and 2 show the mean scores of the research variables in the three stages of pre-test, post-test, and follow-up in the three groups of adolescent-centered mindfulness, cognitive behavioral therapy, and control.

As seen in Figure 1 and Figure 2, both the suicidal ideation and depression mean scores of the cognitive behavioral therapy group were lower than those in the mindfulness therapy group. Thus, it seems that the effect of mindfulness training and cognitive behavioral therapy was significant on depression and suicidal ideations in adolescent girls with bipolar disorder in the post-test phase. Cognitive behavioral therapy was more effective in both of these variables in both the post-test and follow-up stages of adolescent-centered mindfulness training.

Discussion

Bipolar disorder is a chronic and debilitating disease that disrupts patients’ social functioning. In this study, we compared cognitive behavioral therapy with mindfulness therapy to improve depression symptoms, and suicidal ideation in adolescent girls with bipolar disorder, and the results showed that both adolescents’ mindfulness training and cognitive therapy intervention were effective in improving suicidal ideation and depression in both post-test and follow-up stages. However, the effect of cognitive behavioral therapy on both variables was greater in both stages. The findings of the study are consistent with Jannetti et al., Hollon, Tice, and Markowitz, and Townsend, regarding the efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy on the improvement of various symptoms of bipolar disorder [20-22].

Regarding the effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy, changing the way of thinking and behaving, cognitive behavioral therapy has fundamental effects on one’s emotional states and changes in depression and anxiety [29]. In other words, based on a cognitive perspective, disorders are the result of false, unrealistic, and irrational beliefs. Cognitive perspectives, such as the psychodynamic perspective, focus on internal flows as causes of disorders, but instead of emphasizing the desires, needs, and motivations, they believe that individuals interpret the information received and use it to solve life’s problems.

The cognitive perspective generally focuses on one’s current thoughts and solutions rather than one’s history. This means that one’s cognitive history, attitudes, and his or her present mood are considered as causes of disorders [30]. This treatment helps clients identify automatic thoughts, images, or thoughts that trigger the disorders, observe the rationale and misconceptions underlying these thoughts, and test their validity [31].

The cognitive behavioral therapy model emphasizes three main strategies of training, cognitive restructuring, and life skills intervention. In training methods, individuals are taught to identify and deal with high-risk situations that increase the likelihood of loss of control or threat of return. Cognitive restructuring is about changing one’s perception of abstinence or slip. If it does come back, instead of treating it as a personal failure that leads to internal guilt and attribution. The patient is taught to “rebuild this event as a single, independent event, and to call it an error, not a disaster that can never be overcome”. Teaching problem-solving skills to adolescents provides essential skills to solve social problems without resorting to aggression, and empathy training in schools, especially in adolescence, can reduce aggressive behaviors. Using empathy, one can identify the consequences of their behavior and thereby respond to the demands of others [32].

The findings of the present study on the efficacy of adolescent-centered mindfulness therapy are consistent with the results of Zeidan et al., who have shown that mindfulness improves mood, and short-term use of it could reduce fatigue and anxiety. Likewise, the findings of Chow et al. and Seigel showed that mindfulness-based interventions were effective in patients with bipolar disorder and would reduce anxiety and depression in them [16-18].

Concerning this finding, mind control skills learned in mindfulness can prevent the recurrence of major depression. In this treatment, people do not judge their thoughts and feelings and view them as mental events that are on the move and do not necessarily represent aspects of themselves or reality. In this approach, it is assumed that individuals learn how not to get caught up in their malicious thought patterns [33].

Mindfulness is taught through a series of tasks that are self-conscious. Each exercise can intentionally and consciously increase the capacity and ability of the information system. Mindfulness exercises can act as an early warning system to prevent a blast or an imminent flood. Mindfulness training requires metacognitive learning and new behavioral strategies to focus on attention, avoid malicious thoughts, and the tendency toward worrying responses. It also promotes new thinking and reduces emotions.

One of the fundamental orientations of mindfulness consciousness is focusing on the “present moment”. This “here and now” orientation has been effective in helping patients with cancer and chronic pain [34]. When the subjects are aware of the present, their attention is no longer focused on the past or the future; thus, suicidal ideations reduce, while most of the psychological problems rooted in focusing on their past.

In explaining the efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy rather than mindfulness therapy in improving depression and suicidal ideation in the study sample, symptoms of bipolar disorder are often characterized by inhibition, lack of energy, and apathy, all of which are behavioral symptoms; therefore, it is better to prioritize these behavioral methods [35]. Behavioral therapies are more effective in controlling patients’ lives after they have been stabilized with the help of medication. Also, Mansell et al. suggested that cognitive behavioral therapy was useful in the treatment of bipolar disorder for several reasons [36]. First, because of its mental training nature that makes it suitable for the chronic and recurrent disease through promotion, revision, and self-regulation; second, because of its proven efficacy in adhering to treatment; and third is the efficacy of therapy in preventing the relapse.

Based on the study results, we suggest that cognitive behavioral therapy be used in counseling and psychotherapy centers (clinical settings) for adolescent girls with bipolar disorder II to reduce suicidal ideation and depression and to organize counselors and therapists with this approach. It is also recommended that these approaches be tested on other groups to validate them with greater confidence. Other tools, besides questionnaires, should also be used to collect data. On the other hand, any research has its limitations, and the interpretation of the results should be considered in light of these limitations. One of the limitations of this study is the generalization of these results to other groups, as the statistical population of this study was female adolescents with bipolar II disorder.

Conclusion

The results showed that both adolescent-centered mindfulness training and cognitive behavioral therapy significantly reduced suicidal ideation and depression in adolescents with bipolar disorder in the post-test and follow-up stages. Besides, cognitive behavioral therapy in both post-test and follow-up stages was more effective than adolescent-centered mindfulness training in reducing adolescent suicidal ideation and depression.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (Code: No.IR.IAU.KHUISF.REC.1397.028). All the study procedures were in compliance with the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki (2013 revision).

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors contributions

Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content, final approval of the study, conception and design of the study, collection: Bahar Shayegh Borojeni; Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content, final approval of the study, analysis and interpretation of data, collection, and provision of patients: Gholamreza Manshaee; Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content, final approval of the study: Illnaz Sajjadian.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest

References

American Psychiatric Association (APA). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition, (DSM-5). Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association (APA); 2013.

Shaw JA, EJA EJ. A 10-years prospective study of prodromal patterns of bipolar disorder among Amish youth. J Am Acad Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2005; 44(11): 1104-11. [DOI:10.1097/01.chi.0000177052.26476.e5] [PMID]

Swann AC. Mechanisms of impulsivity in bipolar disorder and related illness. Epid Psychiatry Soc. 2010; 19(2):120-30. [DOI:10.1017/S1121189X00000828] [PMID]

Manshee gH, Hoseini L. The effectiveness of child-centered mindfulness training on social adjustment and depression symptoms in children with depression. JEEP . 2018; 29(8):179-200.

Shakibaii fEM. Epidemiology of depression in Isfahan middle school students in 2007-2008. Behav Sci Res. 2014; 12(2):274-84.

Conus P, Ward J, Hallam KT, Lucas N, Macneil C, McGorry PD, et al. The proximal prodrome to first episode mania - a new target for early intervention. Bipolar Disorders. 2008; 10(5):555-65. [DOI:10.1111/j.1399-5618.2008.00610.x] [PMID]

Lewis L, Judd MD, Hagop S, Akiskal MD, Pamela J. Schettler, et al. A prospective investigation of the natural history of the long-term weekly symptomatic status of bipolar II disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003; 60(3):261-9. [DOI:10.1001/archpsyc.60.3.261] [PMID]

Bridge GB. Adolescent suicide and suicidal behavio. child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006; 47(3-4):372-94. [DOI:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01615.x] [PMID]

Liu X TJ. Life events, psychopathology, and suicidal behavior in Chinese adolescents. Affe Dis. 2005; 86(2-3):195-203. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2005.01.016] [PMID]

Nouk M. Suicide [Internet]. 2006 [updated 2014 July]. Avalible from: http://www.teenshealth.com

Zaretsky A. Targeted psychosocial intervention for bipolar disorder. Bip Dis. 2003; 5(2):80-7. [DOI:10.1111/j.1399-2406.2003.00057.x] [PMID]

Roth BR. Mindfulnessbased stress reduction and health related quality of life. Psyc Med. 2004; 66(1):113-23. [DOI:10.1097/01.PSY.0000097337.00754.09] [PMID]

Semple R, Lee J. Mindfulness based congnitive therapy for children. In: Baer RA, editor. Mindfulness-Based Treatment Approaches. New York: Application Across the LIFESPAN; 2014. [DOI:10.1016/B978-0-12-416031-6.00008-6]

Amber S, Emanuel J, Updegraff D, Kalmbach J, Ciesla. The role of mindfulness facets in affective forecasting. Pers and Ind Diff. 2010; 49(17):815-818. [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2010.06.012]

Burdick D. Mindfulness for kids & teens: A workbook for clinicians & clients with 154 Tools, techniques, activities & worksheets. Wisconsin: PESI Publishing & Media; 2014.

Zeidan F, Johnson SK, Diamond BJ, David Z, Goolkasian P. Mindfulness meditation improves cognition: Evidence of brief mental training. Consc Cog. 2010; 19(2):597-605. [DOI:10.1016/j.concog.2010.03.014] [PMID]

Siegel L. The mindfulness Solution, every day practices for every day problems. Los Angeles: Guilford Press; 2010.

Chu CS, Stubbs B, Chen TY, Tang CH, Li DJ, Yang WC. The effectiveness of adjunet mindfulness - based intervention in tretment of bipolar disorder: Asystematic review andmeta -analysis. J of Affe Dis. 2018; 225: 234-45. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2017.08.025] [PMID]

Siotis P. Cognitive-behavioral therapy: Applications for the management of bipolar disorder. Bip Dis. 2001; 3(1):1-10. [DOI:10.1034/j.1399-5618.2001.030101.x] [PMID]

Jannati sh, Hosseini F, Kashani A, Seifi H. [The effectiveness of group therapy on cognitive - behavioral therapy on depression and anxiety an self esteem in patients with type I disease disorder (Persian)]. Princ Ment Health. 2017; 19(2):108-13.

Hollon SD, Thase ME, Markowitz JC. treatment and prevention of depression. Psychol Sci. 2002; 3(2):39-40. [DOI:10.1111/1529-1006.00008] [PMID]

Townsend DSN, Mary C. Essential of psychiatric mental heath nursing. Philadelphia: Davis Company; 2008.

Bordeaux. A guide to teaching minfulness skills to childrenand young people. Edinburgh: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2017.

Basco MRA. Cognitive behavioral therapy for Bipolar disorder, 2nd Edition. New-York: Guiford Press; 2007.

Salehzadeh M. [Effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy on depression and quality of life in patients with drug resistant epilepsy in Isfahan (Persian)] [MSc. thesis]. Isfahan: Isfahan University; 2008.

Fathi Ashtiyani A. [Psychological Test- Personality Evaluation and mental Health (Persian)]. Tehran: Besat Publications; 2007.

Beck AT, Steer RA. Beck Anxiety Inventory Manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation Harcourt Brace & Company; 1993.

Anisi J, Fathi Ashtiyani A, Salimi Sh, Ahmadi Kh. Validity and reability of Beck suicidal thought in soldiers. Mil Med. 2003; 33(7):1-37.

Morrison AP. A casebook of cognitive therapy for psychosis. 1st ed. New York: Brunner-Routledge Taylor and Francis Group; 2002.

Azad H. [Abnormal psychology (Persian)]. Tehran: Besat Publications; 2008.

Dadsetan P. [Developmental abnormal psychology (Persian)]. Tehran: SAMT; 2008.

Maina G, Rosso A, Aguglia DF, Chiodelli F, Bogetto. Anxiety and bipolar disorders: Epidemiological and clinical aspects. Giorn Ital Psicopat. 2011; 17:365-75.

Teasdale JD, Moore RG, Hayhurst H, Pope M, Williams S, Segal ZV. Metacognitive awareness and prevention of relapse in depression: Empirical evidence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002; 70(2):275-87. [DOI:10.1037//0022-006X.70.2.275] [PMID]

Speca M, Carleson LE, Mackenzie MJ, Angen M. Mingfulnessstress duction (MBSR) as an interventionfor cancer patients. In: bear. R. editor. Mindfulness based treatment approaches. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2006. [DOI:10.1016/B978-012088519-0/50012-5]

Zaretsky AE, Segal ZV, Gemar M. Cognitive therapy for Bipolar depression: A pilot study. Can J Psychiatry. 1999; 44(5):491-4. [DOI:10.1177/070674379904400511] [PMID]

Mansell W, Colom F, Scott J. The nature and treatment of depression in Bipolar disorder: A review and implications for future psychological investigation. Clin Psychol Rev. 2005; 25(8):1076-100. [DOI:10.1016/j.cpr.2005.06.007] [PMID]

Type of Study: Research |

Subject:

Special

Received: 2019/04/17 | Accepted: 2019/06/23 | Published: 2019/10/1

Received: 2019/04/17 | Accepted: 2019/06/23 | Published: 2019/10/1

| Rights and permissions | |

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |