Thu, Apr 25, 2024

Volume 5, Issue 2 (Spring 2019)

Caspian J Neurol Sci 2019, 5(2): 66-72 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Nasiri J, Ghazavi M, Yaghini O, Poormasjedi S, Ghadimi K, Masaeli M F. Risk Factors of Idiopathic Language Development Disorders in Children. Caspian J Neurol Sci 2019; 5 (2) :66-72

URL: http://cjns.gums.ac.ir/article-1-241-en.html

URL: http://cjns.gums.ac.ir/article-1-241-en.html

Jafar Nasiri *

1, Mohammadreza Ghazavi2

1, Mohammadreza Ghazavi2

, Omid Yaghini2

, Omid Yaghini2

, Sobhan Poormasjedi3

, Sobhan Poormasjedi3

, Keyvan Ghadimi3

, Keyvan Ghadimi3

, Mohammad Farid Masaeli3

, Mohammad Farid Masaeli3

1, Mohammadreza Ghazavi2

1, Mohammadreza Ghazavi2

, Omid Yaghini2

, Omid Yaghini2

, Sobhan Poormasjedi3

, Sobhan Poormasjedi3

, Keyvan Ghadimi3

, Keyvan Ghadimi3

, Mohammad Farid Masaeli3

, Mohammad Farid Masaeli3

1- Child Growth and Development Research Center, Research Institute for Primordial Prevention of Non-Communicable Disease, School of Medicine, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran , Nasiri.jafar@gmail.com

2- Child Growth and Development Research Center, Research Institute for Primordial Prevention of Non-Communicable Disease, School of Medicine, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran

3- School of Medicine, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran

2- Child Growth and Development Research Center, Research Institute for Primordial Prevention of Non-Communicable Disease, School of Medicine, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran

3- School of Medicine, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran

Full-Text [PDF 1204 kb]

(848 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2574 Views)

Discussion

Based on the data, it appears that factors such as children’s weight and age; parents’ occupation, main language spoken, and education level; access to television and cell phone; birth order of children, and going to kindergarten do not affect the emergence of LDD in children, whereas a positive family history for LDD may affect its incidence in children. Therefore, having a positive family history can increase the risk of the impairment by >4 folds. Furthermore, the mean age of developmental factors, e.g. smiling, head control, sitting up, walking, and uttering the first words was higher in children with LDD. Although sentence perception was lower in these children, no difference was found between the two groups in terms of language perception.

Mondal et al. [7] examined the prevalence and risk factors of LDD in children <3 years old, and concluded that the prevalence of this disorder is 27% in these children, and factors such as bad housing condition, male gender, and positive family history are significantly associated with this disorder. In our study, results showed that a positive family history is effective in the emergence of LDD. Although the number of boys was higher than girls, no significant difference was observed in terms of gender.

Thomas et al. [8] reported that factors such as low education level of mothers, male gender, and positive family history significantly affected the emergence of LDD in children aged <3 years. Similar results in our study were mother’s low education level which was associated with a higher incidence of LDD. Another study reported that being premature, low weight at birth, mothers’ alcoholism, having a single parent (being widowed, divorced, etc.), and low educational status in parents were risk factors for LDD [12].

In the present study, weight at birth was not found to be a risk factor for LDD because there was no difference between case and control groups in this regard. Furthermore, in the systematic review by Wallace et al. [13], it was concluded that the risk factors for LDD include male gender, positive family history, and low parental education level. It furthermore mentioned that its early diagnosis by a diagnostic instrument can help the timely treatment of patients. Some studies mention that watching TV for a long time LDD or causes psychological disorders [14].

In the present study, access to television and cell phone did not affect speech impairment in children. Those with a positive history for unclear speech, stuttering, delayed language or speech, or poor vocabulary have an almost four-time higher chance of language and speech impairment compared to others, and often an immediate family member suffers from this disorder. Thus, a positive family history is considered to be associated with language and speech impairment [8, 15, 16]. Finally, language and speech delay is often more prevalent in males [17], which is aligned with our finding.

Conclusion

Based on the results of this and previous studies, children’s weight and age; parents’ occupation, main language spoken, and education level; access to television and cell phone; birth order of children, and going to kindergarten do not affect the emergence of LDD in children, while a positive family history for LDD may affect its incidence in children. In addition, a delay in development is associated with LDD. The limitations of this study were failure to examine other risk factors. Further studies on larger samples are required in Iran to confirm the results of the present study.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (No. 397241). All the study procedures were in compliance with the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki 1957.

Funding

The cost of this thesis (No. 397241) was taken by graduate studies at the University of Isfahan in the Research Laboratories of the Department of Biology.

Authors contributions

Conception, collection, critical revision of the article for important intellectual content, Final approval of the study: Jafar Nasiri; Design of the study, provision of study material or patients, Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content, Final approval of the study: Mohammadreza Ghazavi; Collection, critical revision of the article for important intellectual content, Final approval of the study :Omid Yaghini; Interpretation of data, possession of raw data, Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content, Final approval of the study: Sobhan Poormasjedi; Analysis and interpretation of data, Statistical expertise, Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content, Final approval of the study: Keyvan Ghadimi; Provision of study material or patients, collection, Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content, Final approval of the study: Farid Masaeli.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

We thank those who assisted us in conducting this study, including Dr. Bahrami, professor of speech therapy at the Faculty of Rehabilitation Sciences, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences; Ms. Jalili at Novin Speech Therapy Clinic; Ms. Abdollahi, speech therapist at Isfahan Child Growth and Development Research Center, and Ms. Pirmoradian, speech therapist at Imam Hossein Children’s Hospital.

References

National Academies of Sciences Engineering Medicine. Speech and language disorders in children: Implications for the social security administration’s supplemental security Income program. Washington National Academies Press; 2016.

Law J, Boyle J, Harris F, Harkness A, Nye C. Prevalence and natural history of primary speech and language delay: Findings from a systematic review of the literature. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders. 2000; 35:165-88. [PMID]

King TM, Rosenberg LA, Fuddy L, Mcfarlane E, Sia C, Duggan AK. Prevalence and early identification of language delays among at-risk three year olds. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2005; 26(4):293-303. [DOI:10.1097/00004703-200508000-00006]

Sidhu M, Malhi P, Jerath J. Early language development in Indian children: A population-based pilot study. Annals of Indian Academy of Neurology. 2013; 16(3):371. [DOI:10.4103/0972-2327.116937] [PMID] [PMCID]

Sidhu M, Malhi P, Jerath J. Multiple risks and early language development. The Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 2010; 77(4):391-5.[DOI:10.1007/s12098-010-0044-y] [PMID]

Binu A, Sunil R, Baburaj S, Mohandas MK. Sociodemographic profile of speech and language delay up to six years of age in Indian children. International Journal of Medical Research & Health Sciences. 2014; 3(1):98-103. [DOI:10.5958/j.2319-5886.3.1.020]

Mondal N, Bhat BV, Plakkal N, Thulasingam M, Ajayan P, Poorna DR. Prevalence and risk factors of speech and language delay in children less than three years of age. Journal of Comprehensive Pediatrics. 2016; 7(2):e33173.[DOI:10.17795/compreped-33173]

Campbell TF, Dollaghan CA, Rockette HE, Paradise JL, Feldman HM, Shriberg LD, Sabo DL, Kurs-Lasky M. Risk factors for speech delay of unknown origin in 3-year-old children. Child Development. 2003; 74(2):346-57. [DOI:10.1111/1467-8624.7402002] [PMID]

Ozcebe E, Belgin E. Assessment of information processing in children with functional articulation disorders. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology. 2005; 69(2):221-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijporl.2004.09.002] [PMID]

Lewis BA, Freebairn LA, Taylor HG. Follow-up of children with early expressive phonology disorders. Journal of learning Disabilities. 2000; 33(5):433-44. [DOI:10.1177/002221940003300504] [PMID]

Molini-Avejonas DR, Ferreira LV, Amato CA. Advances in speech-language pathology: Risk factors for speech-language pathologies in children. London: Intech Open; 2017. [DOI:10.5772/intechopen.70107]

Delgado CE, Vagi SJ, Scott KG. Early risk factors for preschool speech and language impairments. Exceptionality. 2005; 13(3):173-91. [DOI:10.1207/s15327035ex1303_3]

Wallace IF, Berkman ND, Watson LR, Coyne-Beasley T, Wood CT, Cullen K, et al. Screening for speech and language delay in children 5 years old and younger: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2015; 136(2):e448-62. [DOI:10.1542/peds.2014-3889] [PMID]

Morooka K. Diagnosis of speech retardation and early intervention. Brain and development. 2005; 37(2):131-8. [PMID]

Nelson HD, Nygren P, Walker M, Panoscha R. Screening for speech and language delay in preschool children: Systematic evidence review for the US preventive services task Force. Pediatrics. 2006; 117(2):e298-e319. [DOI:10.1542/peds.2005-1467] [PMID]

Miller CA, Kail R, Leonard LB, Tomblin JB. Speed of processing in children with specific language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2001; 44(2):416-33. [DOI:10.1044/1092-4388(2001/034)]

Stevenson J, Richman N. The prevalence of language delay in a population of three-year-old children and its association with general retardation. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 1976; 18(4):431-41.[DOI:10.1111/j.1469-8749.1976.tb03682.x]

Full-Text: (1088 Views)

Highlights

● A positive family history of language development disorder is effective in the emergence of speech impairment in children.

● Children’s weight and age; parents’ occupation, main language spoken, and education level; access to television and cell phone; birth order of children, and going to kindergarten do not affect language development disorder in children.

Introduction

Speech is a significant experience for human, acquired in a seemingly automatic process starting from birth and continuing to adolescence. Language Development Disorders (LDD) are often diagnosed when the child cannot reach the expected developmental milestones. These disorders disrupt children’s functioning, affecting their communicative ability with serious consequences. In addition, more serious cases of these disorders are expected to continue for the rest of the person’s life [1].

As reported by different writers [2, 3], the prevalence of LDD varies extensively because of the differences in the studied age groups as well as different diagnostic tests and terms for the disorder. LDD may be primary or secondary. Numerous biological and environmental factors, e.g. dissatisfaction, low birth weight, perinatal disorders, low income, and limited parental education are correlated with LDD [4, 5]. There is extensive information on the prevalence and risk factors of LDD in Western countries. However, little information is available on Middle Eastern countries, especially Iran [6]. The prevalence of this disorder in children aged <3 years is relatively higher, about 27%, with an increasing trend [7].

The cause of this disorder is unknown, but certain risk factors such as male gender, positive family history, chronic otitis media, and other factors have been introduced as associated with this disorder [8]. Other factors such as birth weight and head circumference, current head circumference, and access to media may also affect this disorder [7].

Comorbid LDD with various neurological development problems in children are prevalent. These problems include damage resulting from birth asphyxia, cerebral palsy, congenital infections, genetic disorders, intellectual disabilities, and hearing impairment. However, ~14% of children with no specific disease suffer from LDD [8].

LDD must receive timely intervention and treatment. LDD -related skills may be associated with other cognitive disorders such as low IQ, poor information processing skills, and limited literacy skills (such as reading and spelling) [9, 10].

One study reported that factors such as male gender, prematurity, shyness, being an only child, being the youngest child, bad oral habits, a family history of language impairment, and consumption of unsafe medications during pregnancy may affect children’s LDD [11]. The present study aimed to evaluate, for the first time in Isfahan, the risk factors of LDD with idiopathic causes in children. If these factors are effective, they can be prevented or resolved in order to prevent LDD in children.

Materials and Methods

In the present case-control study, 97 children aged two to five years with speech impairment visiting neurology clinics affiliated with Isfahan University of Medical Sciences in fall and winter 2017 who did not have any other problem except speech impairment were selected with convenience sampling method. Moreover, 97 healthy children (in kindergartens or hospitalized for non-neurological reasons) were also selected randomly as the control group.

Inclusion criteria for both groups were the age of two to five years, having no known neurological, oral, or dental problems; birth asphyxia, or brain injury, e.g. head trauma, meningitis, and encephalitis. Patients in the case group had the definitive diagnosis of language development disorders (Code: ICD-10=F80.9) by a pediatric neurologist, and children in the control group did not have any delay in LDD in addition to meeting the inclusion criteria. Children whose parents did not consent to complete the researcher-made checklist or were unwilling to participate were excluded from the study. The parents of eligible children with LDD were briefed and signed consent forms. The researcher-made checklist was completed by a pediatric neurologist based on parents’ responses and examining the children upon their visit to the clinic.

Items covered the child’s gender; parental education level, age, and occupation; access to mass media such as television and cell phone; history of LDD in the family; place of residence; main language of parents; the child’s going to the kindergarten or staying at home, and birth order of children. Moreover, birth weight, current weight and head circumference were measured and recorded. Parents’ language was classified as standard or local. Standard language was defined as the official language of Iran (Persian) with no dialect, and local or non-standard language was defined as specific dialects. Also, if the child had access to mass media such as the television and cell phone for more than 30 minutes a day, access was considered to be positive. Moreover, developmental factors such as the age at head control, smiling, sitting up, walking, and uttering the first word were examined by asking the parents. In addition, current language perception (saying words or sentences or lack thereof) was examined in children.

Statistical analysis

Data were entered into SPSS V. 22, and Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was run to check the normality of data distribution. To compare quantitative and qualitative data between the two groups, independent samples t-test and Chi-squared test were used, respectively. Quantitative data are expressed as mean and SD, while qualitative data are represented as frequency or frequency percentage. Logistic regression was also run, and P<0.05 was set as the significance level.

Results

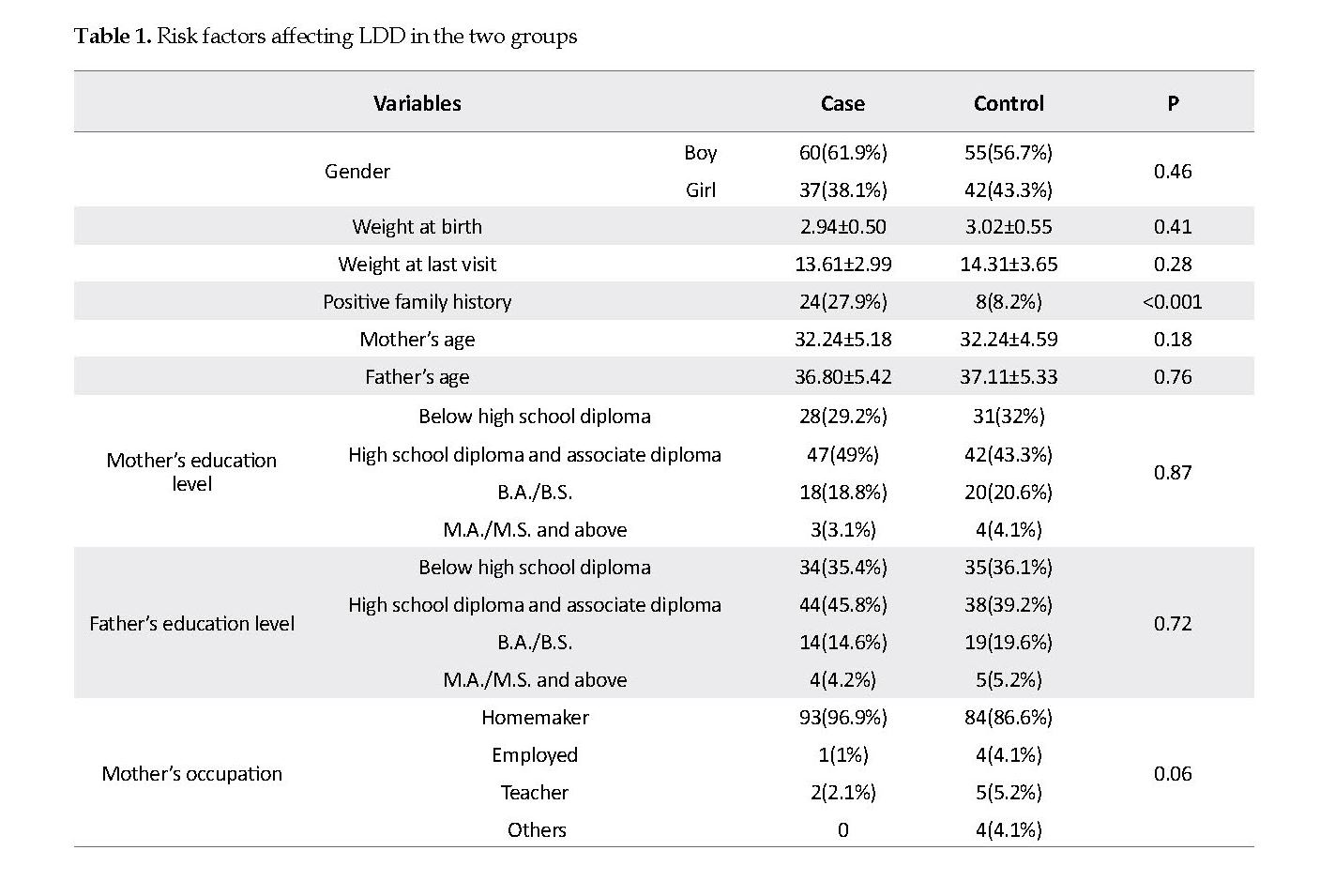

In this study, 97 children participated in the case group (68 boys and 29 girls) and 97 children in the control group (55 boys and 42 girls). No significant difference was observed between the two groups in terms of gender, weight at birth, weight at last visit, and parental age, education level, language, or occupation. Also, no significant difference was observed between the two groups in terms of other risk factors, namely the place of residence, birth order of children, and going to the kindergarten (P>0.05). However, the two groups were significantly different in terms of a positive family history, which was significantly higher in the case than that in the control group (P<0.05) (Table 1).

● A positive family history of language development disorder is effective in the emergence of speech impairment in children.

● Children’s weight and age; parents’ occupation, main language spoken, and education level; access to television and cell phone; birth order of children, and going to kindergarten do not affect language development disorder in children.

Introduction

Speech is a significant experience for human, acquired in a seemingly automatic process starting from birth and continuing to adolescence. Language Development Disorders (LDD) are often diagnosed when the child cannot reach the expected developmental milestones. These disorders disrupt children’s functioning, affecting their communicative ability with serious consequences. In addition, more serious cases of these disorders are expected to continue for the rest of the person’s life [1].

As reported by different writers [2, 3], the prevalence of LDD varies extensively because of the differences in the studied age groups as well as different diagnostic tests and terms for the disorder. LDD may be primary or secondary. Numerous biological and environmental factors, e.g. dissatisfaction, low birth weight, perinatal disorders, low income, and limited parental education are correlated with LDD [4, 5]. There is extensive information on the prevalence and risk factors of LDD in Western countries. However, little information is available on Middle Eastern countries, especially Iran [6]. The prevalence of this disorder in children aged <3 years is relatively higher, about 27%, with an increasing trend [7].

The cause of this disorder is unknown, but certain risk factors such as male gender, positive family history, chronic otitis media, and other factors have been introduced as associated with this disorder [8]. Other factors such as birth weight and head circumference, current head circumference, and access to media may also affect this disorder [7].

Comorbid LDD with various neurological development problems in children are prevalent. These problems include damage resulting from birth asphyxia, cerebral palsy, congenital infections, genetic disorders, intellectual disabilities, and hearing impairment. However, ~14% of children with no specific disease suffer from LDD [8].

LDD must receive timely intervention and treatment. LDD -related skills may be associated with other cognitive disorders such as low IQ, poor information processing skills, and limited literacy skills (such as reading and spelling) [9, 10].

One study reported that factors such as male gender, prematurity, shyness, being an only child, being the youngest child, bad oral habits, a family history of language impairment, and consumption of unsafe medications during pregnancy may affect children’s LDD [11]. The present study aimed to evaluate, for the first time in Isfahan, the risk factors of LDD with idiopathic causes in children. If these factors are effective, they can be prevented or resolved in order to prevent LDD in children.

Materials and Methods

In the present case-control study, 97 children aged two to five years with speech impairment visiting neurology clinics affiliated with Isfahan University of Medical Sciences in fall and winter 2017 who did not have any other problem except speech impairment were selected with convenience sampling method. Moreover, 97 healthy children (in kindergartens or hospitalized for non-neurological reasons) were also selected randomly as the control group.

Inclusion criteria for both groups were the age of two to five years, having no known neurological, oral, or dental problems; birth asphyxia, or brain injury, e.g. head trauma, meningitis, and encephalitis. Patients in the case group had the definitive diagnosis of language development disorders (Code: ICD-10=F80.9) by a pediatric neurologist, and children in the control group did not have any delay in LDD in addition to meeting the inclusion criteria. Children whose parents did not consent to complete the researcher-made checklist or were unwilling to participate were excluded from the study. The parents of eligible children with LDD were briefed and signed consent forms. The researcher-made checklist was completed by a pediatric neurologist based on parents’ responses and examining the children upon their visit to the clinic.

Items covered the child’s gender; parental education level, age, and occupation; access to mass media such as television and cell phone; history of LDD in the family; place of residence; main language of parents; the child’s going to the kindergarten or staying at home, and birth order of children. Moreover, birth weight, current weight and head circumference were measured and recorded. Parents’ language was classified as standard or local. Standard language was defined as the official language of Iran (Persian) with no dialect, and local or non-standard language was defined as specific dialects. Also, if the child had access to mass media such as the television and cell phone for more than 30 minutes a day, access was considered to be positive. Moreover, developmental factors such as the age at head control, smiling, sitting up, walking, and uttering the first word were examined by asking the parents. In addition, current language perception (saying words or sentences or lack thereof) was examined in children.

Statistical analysis

Data were entered into SPSS V. 22, and Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was run to check the normality of data distribution. To compare quantitative and qualitative data between the two groups, independent samples t-test and Chi-squared test were used, respectively. Quantitative data are expressed as mean and SD, while qualitative data are represented as frequency or frequency percentage. Logistic regression was also run, and P<0.05 was set as the significance level.

Results

In this study, 97 children participated in the case group (68 boys and 29 girls) and 97 children in the control group (55 boys and 42 girls). No significant difference was observed between the two groups in terms of gender, weight at birth, weight at last visit, and parental age, education level, language, or occupation. Also, no significant difference was observed between the two groups in terms of other risk factors, namely the place of residence, birth order of children, and going to the kindergarten (P>0.05). However, the two groups were significantly different in terms of a positive family history, which was significantly higher in the case than that in the control group (P<0.05) (Table 1).

Children’s access to television and cell phone was also assessed, showing no significant difference in terms of level and mean hours of access (P>0.05) (Table 2). Developmental factors, such as the age at head control, smiling, sitting up, walking, and uttering the first word were also examined. Mean age of onset of these actions was significantly higher in the case than the control group (P<0.05). Although the level of sentence perception was higher in the control group, no significant difference was found between the groups in terms of language perception (Table 3).

Based on logistic regression, having a positive family history increased the risk of LDD by 4.45 folds. On the other hand, no significant correlation was found between the age of onset of smiling, sitting up, and walking with LDD (P<0.05), but a significant correlation was found between age of head control and uttering the first word with the noted impairment (P<0.05) (Table 4).

Discussion

Based on the data, it appears that factors such as children’s weight and age; parents’ occupation, main language spoken, and education level; access to television and cell phone; birth order of children, and going to kindergarten do not affect the emergence of LDD in children, whereas a positive family history for LDD may affect its incidence in children. Therefore, having a positive family history can increase the risk of the impairment by >4 folds. Furthermore, the mean age of developmental factors, e.g. smiling, head control, sitting up, walking, and uttering the first words was higher in children with LDD. Although sentence perception was lower in these children, no difference was found between the two groups in terms of language perception.

Mondal et al. [7] examined the prevalence and risk factors of LDD in children <3 years old, and concluded that the prevalence of this disorder is 27% in these children, and factors such as bad housing condition, male gender, and positive family history are significantly associated with this disorder. In our study, results showed that a positive family history is effective in the emergence of LDD. Although the number of boys was higher than girls, no significant difference was observed in terms of gender.

Thomas et al. [8] reported that factors such as low education level of mothers, male gender, and positive family history significantly affected the emergence of LDD in children aged <3 years. Similar results in our study were mother’s low education level which was associated with a higher incidence of LDD. Another study reported that being premature, low weight at birth, mothers’ alcoholism, having a single parent (being widowed, divorced, etc.), and low educational status in parents were risk factors for LDD [12].

In the present study, weight at birth was not found to be a risk factor for LDD because there was no difference between case and control groups in this regard. Furthermore, in the systematic review by Wallace et al. [13], it was concluded that the risk factors for LDD include male gender, positive family history, and low parental education level. It furthermore mentioned that its early diagnosis by a diagnostic instrument can help the timely treatment of patients. Some studies mention that watching TV for a long time LDD or causes psychological disorders [14].

In the present study, access to television and cell phone did not affect speech impairment in children. Those with a positive history for unclear speech, stuttering, delayed language or speech, or poor vocabulary have an almost four-time higher chance of language and speech impairment compared to others, and often an immediate family member suffers from this disorder. Thus, a positive family history is considered to be associated with language and speech impairment [8, 15, 16]. Finally, language and speech delay is often more prevalent in males [17], which is aligned with our finding.

Conclusion

Based on the results of this and previous studies, children’s weight and age; parents’ occupation, main language spoken, and education level; access to television and cell phone; birth order of children, and going to kindergarten do not affect the emergence of LDD in children, while a positive family history for LDD may affect its incidence in children. In addition, a delay in development is associated with LDD. The limitations of this study were failure to examine other risk factors. Further studies on larger samples are required in Iran to confirm the results of the present study.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (No. 397241). All the study procedures were in compliance with the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki 1957.

Funding

The cost of this thesis (No. 397241) was taken by graduate studies at the University of Isfahan in the Research Laboratories of the Department of Biology.

Authors contributions

Conception, collection, critical revision of the article for important intellectual content, Final approval of the study: Jafar Nasiri; Design of the study, provision of study material or patients, Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content, Final approval of the study: Mohammadreza Ghazavi; Collection, critical revision of the article for important intellectual content, Final approval of the study :Omid Yaghini; Interpretation of data, possession of raw data, Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content, Final approval of the study: Sobhan Poormasjedi; Analysis and interpretation of data, Statistical expertise, Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content, Final approval of the study: Keyvan Ghadimi; Provision of study material or patients, collection, Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content, Final approval of the study: Farid Masaeli.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

We thank those who assisted us in conducting this study, including Dr. Bahrami, professor of speech therapy at the Faculty of Rehabilitation Sciences, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences; Ms. Jalili at Novin Speech Therapy Clinic; Ms. Abdollahi, speech therapist at Isfahan Child Growth and Development Research Center, and Ms. Pirmoradian, speech therapist at Imam Hossein Children’s Hospital.

References

National Academies of Sciences Engineering Medicine. Speech and language disorders in children: Implications for the social security administration’s supplemental security Income program. Washington National Academies Press; 2016.

Law J, Boyle J, Harris F, Harkness A, Nye C. Prevalence and natural history of primary speech and language delay: Findings from a systematic review of the literature. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders. 2000; 35:165-88. [PMID]

King TM, Rosenberg LA, Fuddy L, Mcfarlane E, Sia C, Duggan AK. Prevalence and early identification of language delays among at-risk three year olds. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2005; 26(4):293-303. [DOI:10.1097/00004703-200508000-00006]

Sidhu M, Malhi P, Jerath J. Early language development in Indian children: A population-based pilot study. Annals of Indian Academy of Neurology. 2013; 16(3):371. [DOI:10.4103/0972-2327.116937] [PMID] [PMCID]

Sidhu M, Malhi P, Jerath J. Multiple risks and early language development. The Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 2010; 77(4):391-5.[DOI:10.1007/s12098-010-0044-y] [PMID]

Binu A, Sunil R, Baburaj S, Mohandas MK. Sociodemographic profile of speech and language delay up to six years of age in Indian children. International Journal of Medical Research & Health Sciences. 2014; 3(1):98-103. [DOI:10.5958/j.2319-5886.3.1.020]

Mondal N, Bhat BV, Plakkal N, Thulasingam M, Ajayan P, Poorna DR. Prevalence and risk factors of speech and language delay in children less than three years of age. Journal of Comprehensive Pediatrics. 2016; 7(2):e33173.[DOI:10.17795/compreped-33173]

Campbell TF, Dollaghan CA, Rockette HE, Paradise JL, Feldman HM, Shriberg LD, Sabo DL, Kurs-Lasky M. Risk factors for speech delay of unknown origin in 3-year-old children. Child Development. 2003; 74(2):346-57. [DOI:10.1111/1467-8624.7402002] [PMID]

Ozcebe E, Belgin E. Assessment of information processing in children with functional articulation disorders. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology. 2005; 69(2):221-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijporl.2004.09.002] [PMID]

Lewis BA, Freebairn LA, Taylor HG. Follow-up of children with early expressive phonology disorders. Journal of learning Disabilities. 2000; 33(5):433-44. [DOI:10.1177/002221940003300504] [PMID]

Molini-Avejonas DR, Ferreira LV, Amato CA. Advances in speech-language pathology: Risk factors for speech-language pathologies in children. London: Intech Open; 2017. [DOI:10.5772/intechopen.70107]

Delgado CE, Vagi SJ, Scott KG. Early risk factors for preschool speech and language impairments. Exceptionality. 2005; 13(3):173-91. [DOI:10.1207/s15327035ex1303_3]

Wallace IF, Berkman ND, Watson LR, Coyne-Beasley T, Wood CT, Cullen K, et al. Screening for speech and language delay in children 5 years old and younger: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2015; 136(2):e448-62. [DOI:10.1542/peds.2014-3889] [PMID]

Morooka K. Diagnosis of speech retardation and early intervention. Brain and development. 2005; 37(2):131-8. [PMID]

Nelson HD, Nygren P, Walker M, Panoscha R. Screening for speech and language delay in preschool children: Systematic evidence review for the US preventive services task Force. Pediatrics. 2006; 117(2):e298-e319. [DOI:10.1542/peds.2005-1467] [PMID]

Miller CA, Kail R, Leonard LB, Tomblin JB. Speed of processing in children with specific language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2001; 44(2):416-33. [DOI:10.1044/1092-4388(2001/034)]

Stevenson J, Richman N. The prevalence of language delay in a population of three-year-old children and its association with general retardation. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 1976; 18(4):431-41.[DOI:10.1111/j.1469-8749.1976.tb03682.x]

Type of Study: Research |

Subject:

General

Received: 2019/01/2 | Accepted: 2019/03/4 | Published: 2019/04/1

Received: 2019/01/2 | Accepted: 2019/03/4 | Published: 2019/04/1

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |